The Edible City – April

2nd April. Waterlow Park, Highgate

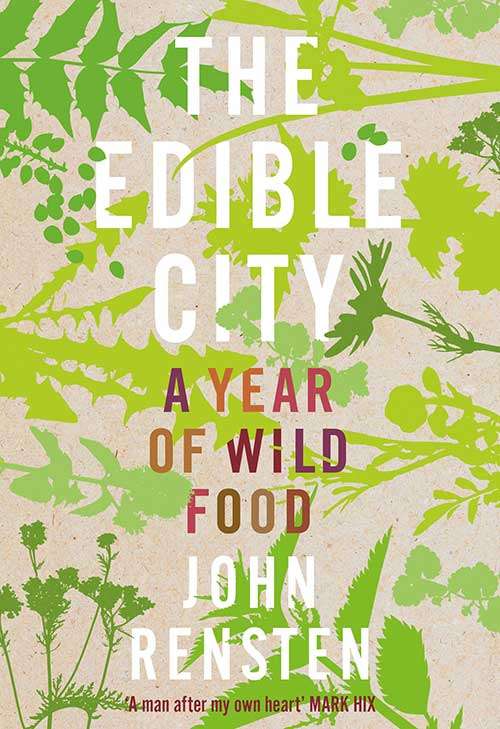

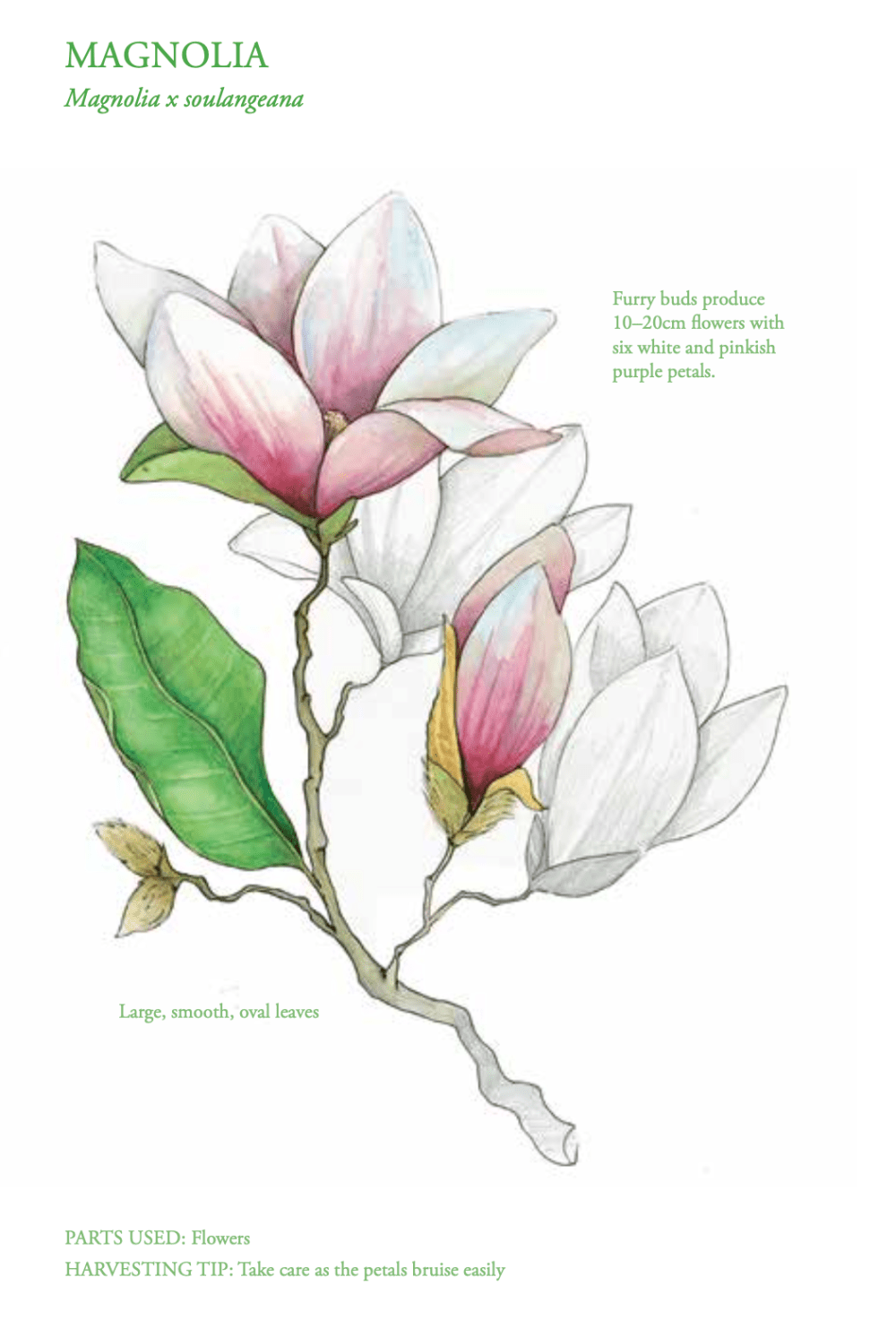

A dense and damp mist was hanging over most of the city this morning and Highgate, which looks like something of a time warp even without it, was positively Dickensian. For various random reasons I seem to have visited this park at regular intervals across the last twenty-five years, once for a picnic, once to break up with a girlfriend, once to clear my head after visiting a friend in the nearby hospital. Today, however, I was on ‘official’ business, meeting with the borough’s ecology officer to discuss running a central London foraging course here. Her caution was understandable, this being a very beautiful and highly manicured little park. ‘Why not just go to Hampstead Heath, it’s full of wild plants, you know?’ A valid question indeed, but it’s the juxtaposition that really interests me, so I took her for a walk, around a place that she knows intimately, and slowly, gently, changed the way she would look at it forever. In roughly an hour, we looked at just over forty species of edible plants, wild and domestic, and we’d only covered a third of the park, getting nowhere near the designated wild area, a small but beautiful nature reserve. In just one spot I found spicy wild garlic, peppery cuckoo flower, sweet- scented lemon balm, wild carrot, winter cress, sweet cicely with a wonderful aroma of aniseed, wild spinach varieties, and so it went on. We looked, touched, rubbed, sniffed and tasted our way through the flower beds, borders and edges, before turning our attentions to the trees, too numerous to list. Her firm favourite, and biggest surprise, was discovering the complicated delights of eating magnolia petals. My work was done, the walk was approved and another person had been converted. I carefully collected a dozen of these amazing flowers, mindful that I was gathering the plant’s reproductive organs and also careful to pick selectively so as not to spoil the view.

Magnolia petals lightly pickled in elderflower vinegar

Spring in a jar. These petals remind me of ginger and also of celery with a bitter hint of chicory, a delicate and complicated flavour indeed. A wild salad has as many surprises as it has ingredients, so some thin slices of magnolia are a great addition. There are over two hundred varieties; mostly in the UK they are deciduous trees and a few evergreens, but I find the taste and texture very similar in all the species I have so far tried. I recently used dried and powdered magnolia petals as an excellent substitute spice when making my son some gingerbread biscuits. They were a terrific success, all consumed the same day. Magnolia can also be used as the base of a floral wine or a fragrant sorbet, but I think there are many more, untapped possibilities for this wonderfully complex ingredient. I find it flowering abundantly in the city from as early as mid-February, so as well as including it in the creation of my wild chai recipe (page 154), I have it in mind to experiment with it as a seasoning for fish cakes, maybe even home-made burgers or sausages.

3 tbsp elderflower vinegar (or 2 tbsp white wine or cider vinegar), 2 tbsp sugar, magnolia blossoms

For this super recipe I used last year’s sweet-scented elderflower vinegar, made simply by leaving half a dozen elderflower sprays in vinegar for a week or so until it takes up their wonderful fragrance. You could just use a white wine or cider vinegar but it will need diluting quite a bit to not overpower the blossoms.

Play with the quantities above but my version is to gently heat the elderflower vinegar or white wine vinegar and sugar together with about six tablespoons of water then leave to cool before adding to roughly enough petals to fill a standard-sized glass jar. They are ready to eat just 12 hours later and, surprisingly, these delicate flowers keep for ages – the colour gets lost but the taste does not. Alternatively, pickle them in rice vinegar and soy; a great recipe for this version is on Robin Harford’s brilliant website www.eatweeds.co.uk. I add them to salads, serve them with cheese or cold meats, or just munch a few each time I walk past the jar.

15th April. Burgess Park

Our Royal Parks are the beautifully manicured jewels in London’s green crown, and a must-see for any visitor to the city. So which one would I take a visitor to – Regent’s Park, Greenwich Park, Hyde Park, Green Park? To be honest, probably none of the above: London has so many less-grandiose patches of green, focal points for local communities, more for everyday use than the ‘best china’ feeling I get from the big four. Imagine a city park that is all things to all people – wide open spaces for sports, tennis courts, a decent cafe with sensible prices, a venue for hire, community food, growing projects, allotments and gardens, a well- thought-out and safe playground, an undulating landscape instead of just flat grassland. Add to this a big lake where fishing is allowed, some woodland, huge flower meadows and wild areas, a running track and even a couple of dozen built-in barbecues . . . welcome to Burgess Park. It has relatively recently been revamped with funds from the national lottery and it’s one of my favourite places in the whole city. Were I to live closer, I would spend all my time there but today, like so many of my visits, was a brief one, just an hour to spare, affording me enough time for a coffee and a wander through the meadows, currently exploding with colour and springtime exuberance. A wild flower meadow, albeit a managed one, creates such a marvellous contrast to its urban setting, calming to the brain, easy on the eye and slowing down the pace of city life from a sprint to a gentle stroll. I drifted around, surrounded by yellow and white ox-eye daisies, newly emerging deep green rocket leaves, white tufts of yarrow and the first of the deep red poppies, but time got the best of me, the phone rang, the spell was broken and I had to dash away.

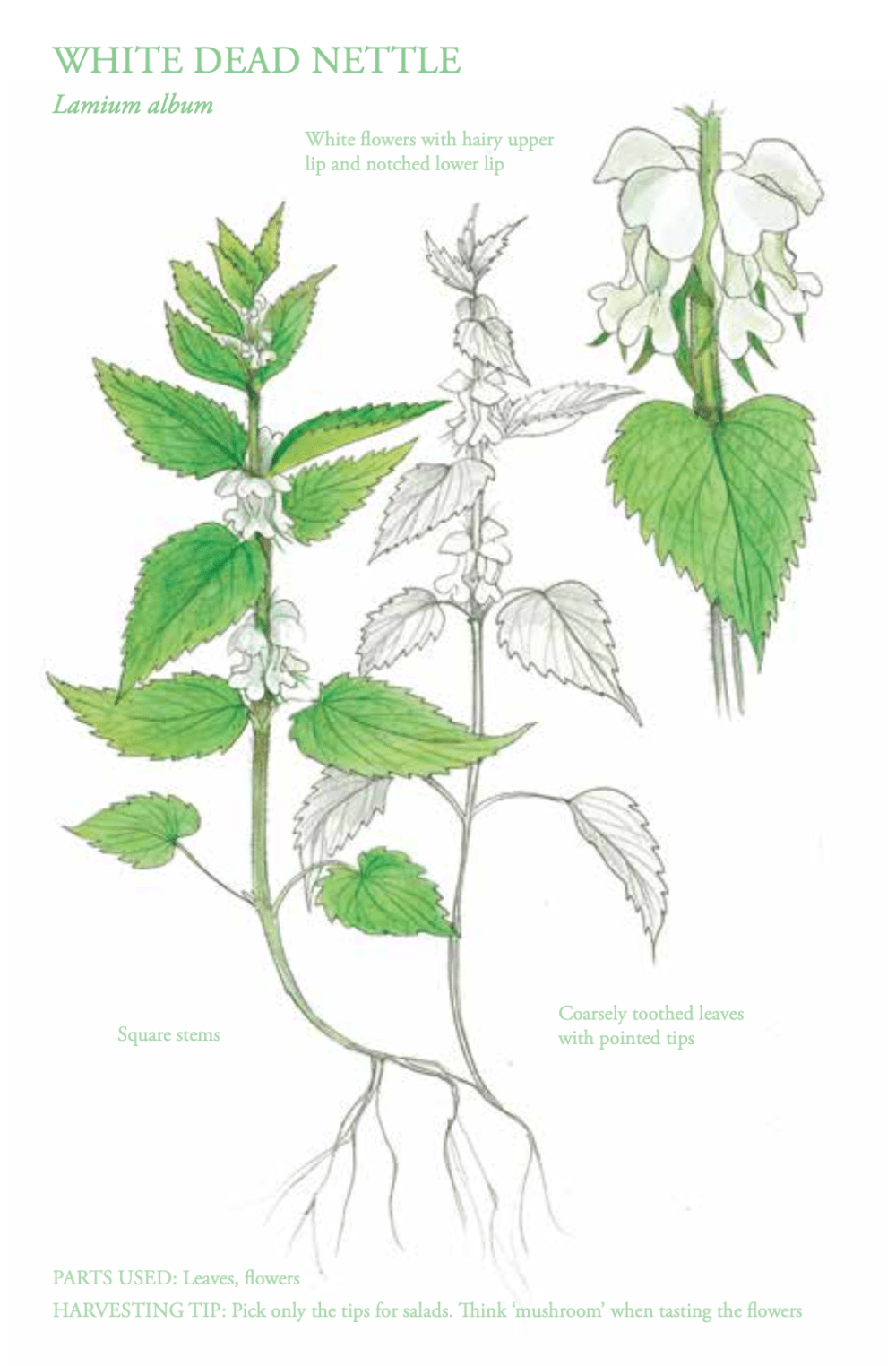

Faced with so much beauty and such variety, without my usual collecting bag, I almost forgot to pick anything at all, but not wanting to leave empty handed, I grabbed a few dozen tempting-looking stems from a patch of one of my favourite city plants – white dead nettle. unrelated to the stinging nettle, lacking its stinging hairs, and very much alive, this is a member of the Mint family with delicious

leaves and flowers available all year round. I took roughly the top 6 inches, which were light green and tender with rings of white flowers growing close to the stem. If nothing else, I had the inspiration for tonight’s dinner.

White nettle ‘risotto’ with sumac and crispy garlic

300–400g white nettle or stinging nettle tops, half a dozen spring onions, 2 garlic cloves, olive oil, 200g long-grain rice, sumac powder, fried garlic, fried seeds (optional), salt and pepper

Serves 2–3

Wild food can be classy food, too, as I remind everyone when the porcini mushroom season comes around. This recipe includes the lovely citrus- tasting buds of the stag horn sumac tree and although they won’t come into flower until later in the year, they are not uncommon in the city. obviously I’d encourage you to pick your own, but in the meantime, sumac powder is readily available in the shops or on the internet. If you’d like to use stinging nettles instead of the non-stinging white dead nettle, you’ll need to get your rubber gloves on to pick and cook them.

Wash and roughly chop the nettle tops but remove the white dead nettle flowers first and keep them for the end. Drop them into about 600ml boiling water for a couple of minutes until they wilt, then drain but keep the water for later.

Finely chop the spring onions and garlic cloves (or any wild garlic varieties you might have) and fry gently in some olive oil, then add the long-grain rice. Stir it for a minute, then add the nettles and twice the volume of the reserved nettle water to rice, covering and simmering it for 10–12 minutes.

When the rice is cooked, season and sprinkle with sumac powder, crispy fried garlic and any other savoury seeds you fancy. Finally, add the flowers of the white dead nettle as a beautiful garnish. To me they taste just like little mushrooms – strange but true.

16th April. Near, but not in, Epping Forest

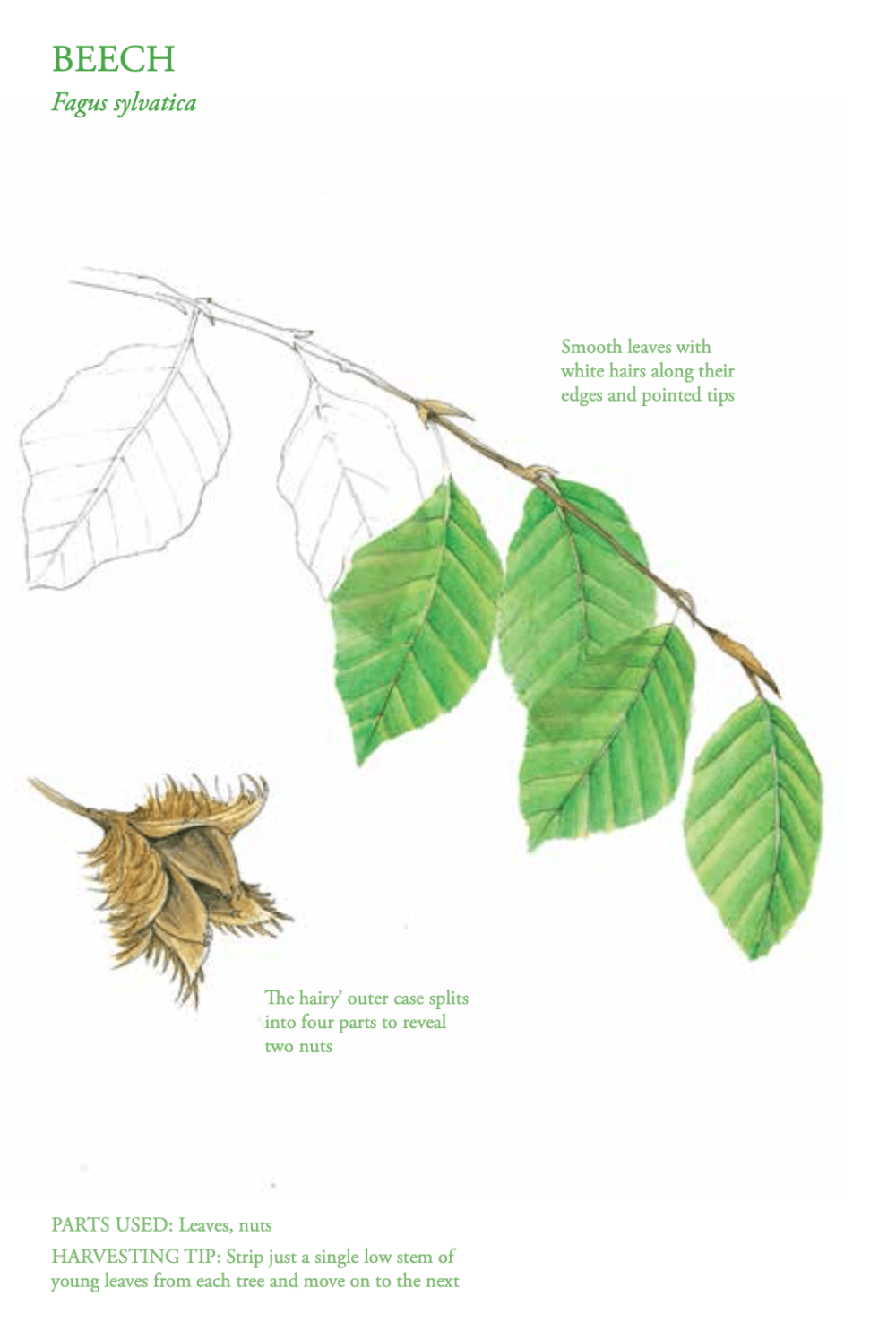

I can think of no greater foraging pleasure than the simplistic and singular task of gathering young beech leaves. A beech forest is a place of calm, part wild but with its own clear sense of order in the natural spacing of the trees, the symbiotic relationships between the woodlands and the fungi that help manage them, the subtle lift in temperature that the forest canopy creates and helps contain. Alas, we have only 2 per cent of our ancient woodland left in the uK so I always feel a huge sense of privilege at being able to walk through such a wonderful part of our landscape, and today was no exception, sunny, slightly chilly, perfect foraging weather. I say my purpose was singular but in all honesty, this is never the way for the enthusiastic forager, constantly aware of what is and what isn’t available, looking for the expected, finding the unexpected, always searching. The newly emerged beech leaves are

pale yellow, translucent and edged with soft, fluffy hairs, drooping downwards from their branches in opposite pairs, tens of thousands of them adorning each enormous tree. I walked the woods, running my hand along the length of just one low branch on every tree I passed, stripping the leaves and dropping them into my bag, almost silent, methodical, gently repetitive. on autopilot, my brain free to wander, I allowed my hands to fill my bag over a period of about an hour, gathering my bounty but leaving no trace of my visit, and no impact on my surroundings, visible or otherwise. At the same time, my eyes were working on the secondary purpose of my visit, to hunt for early St George’s mushrooms or, failing that, signs that they might be on their way. This time I found neither, but was very happy with my haul of deliciously soft leaves, and with their delicate lemony tang they already had me thinking of the various ways I could put them to use.

Beech leaf and chilli infused vodka

Beech leaves, 1 bottle of vodka, 250g sugar, green and red medium- strength chillies

For many years I have made the classic forager’s drink with these leaves, a beech noyau, using gin, sugar and brandy. The result is a deliciously sweet and warming digestif that becomes more flavoursome with age and is the perfect thing to nip from a hip flask on a chilly autumn mushroom hunt, possibly in the same woods the leaves were gathered from. When

I opened the cupboard to hunt for some gin in which to infuse my most recently gathered beech leaves, and found only vodka, I decided it was time for a change.

This recipe is simplicity itself and starts with a large kilner jar or similar vessel. Fill this with young beech leaves, packing in as many as possible, then pour in a whole bottle of vodka, making sure the leaves are covered; add a little water or more vodka if needed. Now leave it to infuse for three weeks, giving it a stir or a prod every so often, turning over the top leaves if they are protruding above the surface. Then strain out the leaves and add sugar water, made by warming 300ml water

and dissolving the sugar in it. Dependent on the size of the bottles you intend to decant into, there should be about two bottles’ worth. I use clear glass with swing tops and into each I add one green and one red medium-strength chilli, deseeded and cut lengthwise into strips. Within 24 hours they have done their work but my last batch is over two years old and they are still in there, admittedly looking rather sad.

The flavour of this drink ‘comes at you’ in three different waves; the sweetness and lemon first, then the medicinal and cleansing feel from the vodka and finally, on the back, a lovely warm chilli heat, which as the drink ages, changes to more of a capsicum taste . . . complex stuff, or so a friend who works as a wine-maker told me.

19th April. A neighbour’s back garden

As I’ve said, I know little to nothing about gardening and other than growing some green veg every so often, it’s just not something I do. In fact, I gave up my small allotment plot because I was always busier picking the wild plants growing around it than the domestic ones in it. This utter lack of knowledge doesn’t stop my neighbours using me as a plant ID service every time something unusual pops up in their gardens, and over the years I have learnt some of the language of the gardener, primarily so as to be able to communicate with a greater audience during the events I run. They say aconite, aquilegia and delphinium, while I would prefer to call these three wolfsbane, columbine and larkspur; when talking wild plants and their historical uses, it’s always more interesting, more informative and just more romantic to use their traditional, sometimes bizarre, names. Who wants to call a plant polygonum when you can use the more descriptive title water pepper, or infinitely better than both, the old English name, Arsesmart! Today I found myself in a neighbour’s back garden, with my three-year-old son Oscar, shouting loudly and running around excitedly, while I tried to work out how to break the news. My opening gambit: ‘Well, the good news is that it’s edible and very tasty.’ I knew exactly what the thirty or so pinky purple spears emerging from the ground were, so reluctantly I told him that we were looking at the dreaded Japanese knotweed, an invasive plant of such destructive powers that it can grow straight up through the pavement, destabilize walls and sometimes render a property uninsurable. With no natural predators in the uK to keep it in check, this plant really is a menace, albeit a very tasty one. I suggested he contact the council, who have very strict rules governing its removal and irradiation, but only after I’d picked a bunch of shoots to take home with me.

Japanese knotweed and beech leaf punch

Imagine a very good rhubarb with the addition of a sharper, more lemony tang – not only is it very tasty but Japanese knotweed is a very versatile plant, too. I have enjoyed such delights as J. K. and apple crumble, J. K. jelly and J. K. flapjacks, and today’s invention, Japanese knotweed and beech leaf punch, using a few tender knotweed shoots no longer than about 10 inches and some of the leftover beech leaves from my recent woodland walk.

6–12 Japanese knotwood shoots, 2 big handfuls of beech leaves, white sugar or pale honey, juice of 1 lemon

This punch is lovely on its own with ice, but also goes well with sparkling water or with chopped fruit or berries added. It could just as easily be made fizzy with a shot of Co2 from a Soda Stream.

Chop the knotweed shoots and cook them together with the young lemony beech leaves in about 1.5 litres of water for 20 minutes. Then stir in some sugar or honey (to taste) and the lemon juice, cool the liquid, strain it and put it in the fridge for 24 hours.

The result, a truly delicious, and original, spring drink, but before deciding to gather Japanese knotweed I would seriously suggest you consider the damage caused by this massively invasive plant and be sure you harvest carefully and responsibly, having read some of the guidelines online. If in any doubt, this recipe works well with just beech leaves or you could use domestic rhubarb instead, but only a little so you don’t overpower the delicate beech flavours. If you’d like to try making a crumble instead, skip forward to September’s blackberry section (page 178) and adapt it accordingly – the addition of super-sweet crème de cassis in this recipe will work wonders with the fruity sharpness of the Japanese knotweed.

27th April. Kensal Green

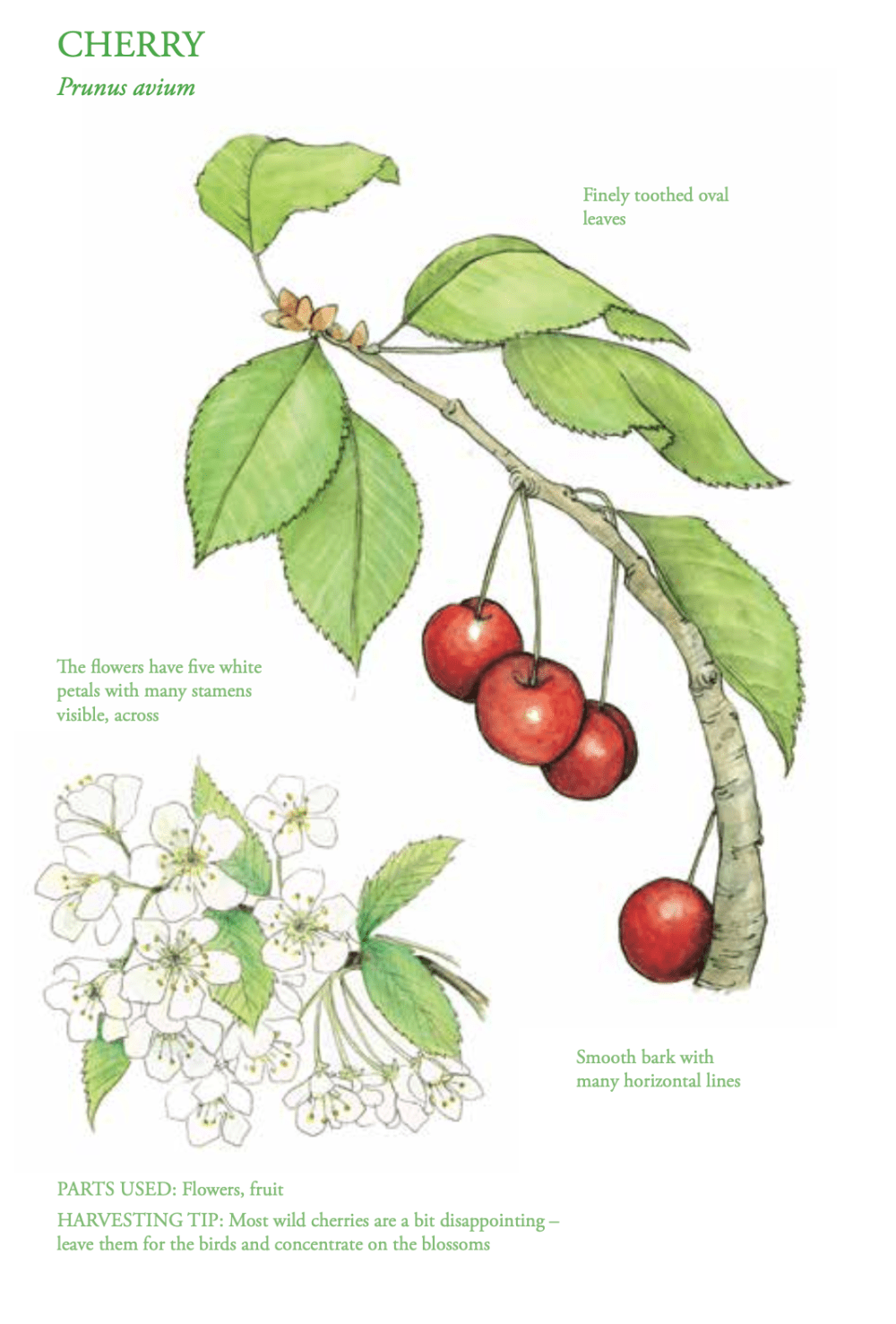

Although an urban family, we spend more time outdoors than most people; the mix of foraging, children’s activities and my wife Ellie’s work as a photographer gives us numerous reasons to leave the house and the omnipresent seduction of computer screens. Today we visited friends across town, at just six or seven miles away; a journey of this sort can take on epic proportions in the city, but today was a Sunday, we were out early and all the traffic hadn’t got out of bed yet. our friends have two young sons so we headed to their local park, the kids going feral, allowing the adults to relax, drink coffee and catch up. Although the park is a place where most people can turn off some of their senses and dial down the machinations of their busy brains, for me it is not, it’s just too full of fascination. A gorgeous avenue of mature cherry trees was calling to me, resplendently swamped with bright pink blossoms, running from almost one side of the park to the other. So grabbing what came to hand, two plastic buckets intended for playing in the sand pit, I went for a wander and gathered as many petals as I could fit into each one, munching a few as I walked. Cherry blossom can taste of three things – sweet, bitter or a delicious almond oil essence – and will often deliver a combination of these in no apparent order. The expression ‘suck it and see’ is very apt. Later I was forced to give up the buckets and decant my blossoms into the hood of Ellie’s coat for the journey home.

Cherry blossom syrup

Of the many varieties of wild cherry I come across, most are a bit sour or have more stone than fruit. Even if you’re lucky enough to find a sweet variety, the birds often strip the trees before they ripen. Cherry blossom, on the other hand, is a far more reliable and plentiful crop, and in Japan it’s harvested commercially to make a similar syrup to this recipe. One of the earlier spring blossoms, it appears from early March until early May with all of the UK varieties being suitable, even the ornamental ones. Making syrup means you don’t need to be too careful, it doesn’t matter if the blossom breaks up, and the variety doesn’t matter either, but if picking in any quantity, avoid taking from just one tree.

Cherry blossom, brown or white sugar

A carrier bag half full of loosely packed blossom is plenty for a batch of syrup. First remove as many leaves and bits of debris as possible, then bring a pan of water to the boil, just enough to cover all the petals, but don’t add them yet. Let the water cool to about 80°C or you’ll ‘burn’ the flowers, ending up with an unpleasant taste. Now pour the hot water over the blossom, just enough to cover, and leave for 24 hours before straining using a jelly bag or fine sieve. Squeeze the blossom to get maximum flavour, then discard and bring the infused water to a boil, reducing the liquid a little to increase the flavour.

Measure the liquid and dissolve the sugar in it at a 1:1 ratio, i.e. into 500ml of liquid dissolve 500g sugar. You may want to experiment with less sugar or adding honey or xylitol instead, but either way you will be rewarded with a wonderful almondy syrup that’s as delicious on vanilla ice cream as it is served as a sauce with red meat.

(Recipe courtesy of fellow forager Peter Studzinski.)