I can think of nothing more fulfilling than cooking with food that I have foraged. To feed yourself and those you care about with ingredients sourced by your own hands is to rekindle a relationship with nature, and the simple act of gathering our own food is the way man has existed for the majority of time on this planet. Although this isn’t an activity that most people associate with living in a twenty-first-century city, I’m sure this book will change the way you look at where you live and allow you to share in some of the wonderful edible experiences that the city has to offer.

It was almost two decades ago that I was properly bitten by the foraging bug, and since then not a day goes by that I don’t pick wild food, study wild food and generally obsess about all things related to wild food. I love sharing what I’ve learnt, running urban foraging walks, taking groups mushroom hunting in the countryside or combing the seashore. For eight years I ran a busy restaurant and revelled in the task of sourcing wild ingredients from outside the city to add to the menu. Eventually I realized that my greatest foraging pleasures were to be found far closer to home and turned my focus onto the place in which I lived.

Don’t be concerned if the idea of eating foraged food in the city feels unsettling at first (take a look at the section on page 259 where we go through all the dos and don’ts, common-sense rules, safety, hygiene and legality to put your mind at rest). I’m certainly not advocating that you only eat foraged foods – even I don’t have time for a totally wild diet. I fit the majority of my foraging into short bursts, shoehorned in between working and looking after my young son. Rather, I want you to see how foraged foods can make an incredible addition to the sorts of meals you are already cooking and eating.

More than simply the good eating it affords, putting on your foraging goggles will transform your city surroundings, from somewhere to be hurried through, to a place to be lingered over. Where previously you’d notice a patch of stinging nettles to sidestep, I want you to see the opportunity to make delicious wild tempura; rather than avoiding that tree that drops annoyingly sticky petals on your car, I hope you’ll spot the chance to make a spring blossom champagne. And that clump of weeds – it doesn’t need clearing, but rather identifying and then incorporating into some wild spring rolls or sushi.

Time spent foraging is as relaxing as it is absorbing; like taking a deep breath, it can bring a feeling of calm to an otherwise frenetic city. Simply walking from my house to the nearest station has become a voyage of discovery, a multi-sensory experience and a treasure hunt, during which I find myself smiling rather a lot.

The standard definition of foraging is this: ‘the act of looking or searching for food or provisions’. The basics are simple and easy to learn, with a good sense of smell being more important than the ability to memorize hundreds of Latin names and complicated plant diagrams. My approach is to take the tiniest bit of knowledge and put it to multiple uses; so simply being able to identify a dandelion will provide countless, year-round foraging opportunities and produce culinary delights as diverse as a caffeine-free coffee, a mid-summer wine, roasted winter root vegetables and spring salads, all from just one, very easy to identify, common as you like, ‘weed’.

You can use this book however you prefer; read it from front to back, all in one go, or dip in sporadically when you have a free moment, heading for the current month, or just pick an ingredient or recipe at random and modify it to suit what’s in season or whatever you currently have access to. Necessity is often called the mother of invention, but availability, for foragers at least, is where the real inspiration lies. The type of cooking that comes from using foraged ingredients is naturally creative, inventive and ad hoc. These won’t be the kind of recipes where things are always measured precisely; ‘a handful’ is often about as accurate as I get.

There are no real rules, other than avoiding the plants that aren’t edible or for whatever reason are not safe to eat, but with enthusiasm and some common sense, a magical side of the city and its hidden larder is waiting to be discovered, probably right on your doorstep. I hope this book takes you on your own food journey, even if it just means you pay a bit more attention to the plants in your local park. With a little effort, it will allow you to begin viewing the city as I do, as a constant source of wonder, an ongoing education and a provider of almost daily inspiration. If foraging teaches us anything, it’s to enjoy and celebrate what is available, not to hanker after what is not.

Where to forage

I live in London and much of the foraging I describe occurs there, but the majority of the plants I pick are in no way specific to the south-east or even the uK. Almost all of them are freely available across northern Europe, actually right across the northern temperate zone, which spans the globe, taking in countries as diverse as North America and Japan. Every country has its own common or local names for these plants, in fact most of them have many variations, so I’ve supplied the Latin names, which are always useful to refer back to in case of any confusion (pages 247–50). once you start to look, you’ll see the real problem is not finding food to forage for but choosing between so many options.

On a spring walk through the unremarkable city park nearest to my house I can easily find lemon balm, spearmint, primrose, white nettle, poppy and yarrow growing at my feet, while above me are avenues of mulberry, hazel, elder, linden, cherry plum and hawthorn trees. Is my local park a particularly outstanding place? Well, yes and no. It has all the things I look for: a mix of well-kept and clean areas, combined with some intentionally ‘wild’ patches and a few less-intentional ones, interesting tree planting and a decent-sized lake, pond or waterway (the border of which is not overly managed). Basically it ticks all the foraging boxes but is no different from another hundred city parks I can think of, so for me, my local park is outstanding, not just for my purposes but for the many other ways in which it provides for the local and wider community. From this one square mile of almost central London, I have identified, collected and eaten nearly 200 different edible plants, many of them giving me multiple crops spread out across the year.

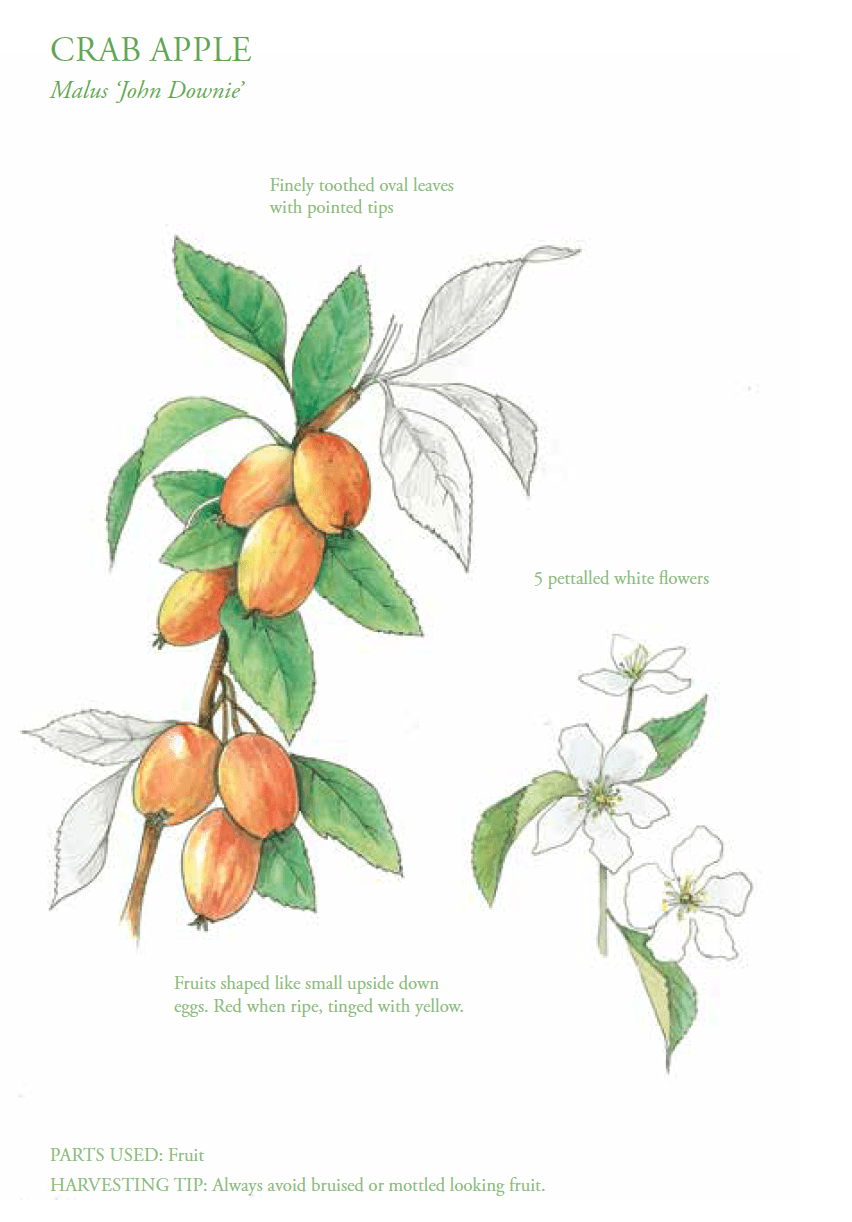

In this book, I take you in detail through sixty of the most common and tastiest, but I reference many, many more.

The plants themselves fall into two, totally non-botanical groups. First, the genuine wild plants, unconcerned with the patchwork of grey blobs that make up the view of London on Google Earth, they are opportunistically able to grow anywhere, colonize a patch of turned- over soil at a moment’s notice or barge their way up through cracks in the pavement. Wild plants don’t need looking after, don’t need feeding, pruning, watering or tending to in any way; robust, hardy, militant, were we to cease to be, I have no doubt that they would reclaim the city at a startling speed. The second group are the ‘unintentionally’ edible or medicinal plants, favoured for planting by both current and Victorian park and town planners, often forming entire avenues of trees or huge lines of bushes. The end result of all this intentional planting – coupled with the prolific growth of wild plants and feral/garden escapees, all thriving in the microclimate that is Greater London – is a huge area of natural diversity, as fertile and bountiful as anywhere else in the country.

Once turned on, your ‘green vision’ will be impossible to turn off; otherwise neglected street trees will suddenly bear fruit, patches of previously irrelevant land will become focal points and the city will reveal a network of free, edible treats, coming and going throughout the year. Things are never as they seem at the first glance and to really see what is in front of us, we need to learn how to look and what to look

for. Do this and the buildings, the cars, the streets and the shades of grey will all fade away to be replaced by a vibrant, fertile landscape, full to the brim with sweet smells, strong flavours and bright colours.

Why forage?

Why indeed, should we be interested in eating any of these plants, with so much food available to us in the city? I can think of a hundred reasons, emotional as well as physical, and most of them will crop up repeatedly in the pages of this book, but for now, let’s just look at nutrition and a simple, irrefutable statement of fact. Wild food is superfood. To clarify this it’s important to define what’s actually meant by ‘superfood’, especially as it’s one of those popular terms that get overused by companies trying to market ‘healthy’ foods. It gives you some idea of how far the food industry has wandered from the path these days that the notion of food being good for you is a distinct selling point, rather than a given. At the same time, 400 generations of farming and a global obsession with growing and eating grains has left us with food that travels well, lasts ages, resists bruising, looks amazing and very often tastes of little to nothing. Since the mid-1950s, when the responsibility for processing and preparation of the majority of our food began to move out of the domestic kitchen and into the hands of big businesses, we have become ever increasingly separated from what we eat. The points of origin, provenance and methods of creation are often unknown and the techniques involved in turning the raw produce of grains, fruits, vegetables and livestock into the meals we ultimately consume are, to most of us, very mysterious.

Furthermore, the vitamins, minerals, proteins, nutrients, fibre, antioxidants and thousands of other phyto-nutrients (more about these later), have been bred out and replaced with our favourite legal high, sugar, to the point where the vast majority of the fruit and veg available to us is utterly stuffed with carbs, and not much else. I’m not claiming this is all the result of a huge global conspiracy – at least it wasn’t initially – it’s just that we like sweet things and as a result we have favoured varieties that give us what we want. I know a respected botanical nutritionist who describes sweetcorn, a plant, like so many, that bears utterly no resemblance to its ancestors, as ‘Nature’s own Mars Bar’. But then again, we wouldn’t want to eat Neolithic sweetcorn, a tough and stony little thing.

Fortunately, like traditional hunter-gatherers, we can go back to nature, where all the wonderful nutrition we need is still waiting for us in abundance and all we have to do is take it. When people talk about a ‘superfood’, what they’re referring to is anything that is extremely rich in minerals and vitamins, particularly beneficial to health and which contains much higher levels of antioxidants and enzymes than other foods, hence being excellent at supporting digestion, promoting healing, detoxification and nutrient absorption, aiding fertility and maintaining general good health. A few of the very common ingredients described as superfoods that are available in the shops include garlic, blueberries, rose hips, dark leafy greens, turmeric, cinnamon and flax. These could be joined by another fifteen to twenty items that are part of our commercial food chain, but were I to write a list of wild superfoods it would be pretty much endless. It’s not that I’m anti mass-production; when massive cities have massive appetites, I appreciate that the food has to come from somewhere, but when over 60 per cent of the world’s calories now come from just four crops (wheat, corn, rice and potatoes) isn’t there room for some more variety in our diets, regardless of the apparent range of choice available to us in the city? obviously these are big issues, where the problems and their solutions are political, and this is a wild food diary, not a selection of hidden agendas, so I won’t be climbing onto my soap box . . . much.

All wild food, however, is superfood: nettles are over 30 per cent plant protein and full of iron and calcium; rose hips have, weight for weight, twenty times the vitamin C of oranges; hazelnuts have five times the protein of eggs; and just one teaspoon of seeds from ribwort plantain, probably the most common and widespread plant I know, has as much fibre as a whole bowl of porridge. I could go on (and on), but none of this would be of much use to anyone if the wild food we picked and ate didn’t taste great, and it does, it really does. If my years running a busy London restaurant taught me one thing, it’s this: flavour is king, and if your ingredients already taste wonderful, then simple cooking and good presentation are really all they need.

How to forage

‘Grazing’ is the loose title I have given to what I do in the city; sampling numerous plants, herbs and other wild foods, but mostly in small amounts, experiencing new flavours and learning how these change with the seasons rather than trying to gather armfuls of one plant when it’s at its best or most obvious. The city parks and pretty much all of our urban green spaces are not common land, but privately owned and managed areas that we are allowed access to, and, leaving the politics of land ownership aside, if we want to forage in these areas, we must respect this, just as we do numerous other guidelines that allow us to coexist in such close proximity to so many other people. obviously, it’s up to the individual, but this is my take on how to treat these places, not to ever take for granted the effort that goes into making them as wonderful as they are.

On all of the foraging walks I organize, the idea of taking whatever knowledge we already have, however small, and gradually adding to it through gentle repetition and multiple encounters with the same plants, is a recurrent theme, a process as far removed from academic study as I can make it. Learn just two or three new plants a month, all of which will have multiple crops and overlapping seasons, and you have access to nearly a hundred edible wild foods, spread throughout the year. My strategy is to make a small amount of knowledge yield a big reward. Through this simple approach I’ve learnt more about nature, foraging, botany, nutrition, ecology and numerous other topics from the one square mile of city greenery that makes up my local park than I have from the rest of the entire country. And how? Proximity and gentle repetition, that’s how. I find it slightly corny to call foraging an art but it does take a very specific skill set, best learnt over an extended period of time, and although later I’ll help you learn to identify fifty wild edible plants in just ten minutes (that’s all the uK’s wild members of the Mint family), this knowledge is the culmination of numerous other things, including many repeated visits to the same places, passing and observing the same plants in all their different stages of growth, the changes of the seasons and how these affect what is, and what isn’t, available.

Take this approach to learning and I guarantee you will simultaneously learn how to forage, to become aware of the seasons, the ‘micro-seasons’ within them, and to look at the city as a network of periphery, borders and edges, not just blocks of adjoining land but overlapping environments that offer increased diversity, fertility and opportunity. once we can ID just a small selection of plants and become familiar with them, their habitats and the visual and physical changes they undergo throughout the year, we reach a point where the botany is almost irrelevant and what remains is a form of recognition akin to spotting a good friend a hundred feet away in a crowd of people.

When we start to investigate the extraordinary array of wild flavours the city has to offer, it soon becomes apparent that rather than living in a place where food remains separated from our day-to-day environment, we are actually surrounded by it: tasty, healthy and hiding in plain sight. Nature not only becomes a vast impulse-purchase section, but one where everything is free and the products are healthy and nutritious. The lemony tang of wild sorrel, the sour-sweetness of wild plums, the joy of finally beating the squirrels to a few hazelnuts and the sheer delight of tasting the first lime blossoms of the year – it’s all there for us, it’s free, it’s fun and it’s absolutely delicious.

Read more