The Edible City – May

3rd May. Springfield Park

It was hot, really deliciously hot, that weekend in early May where the weather pretends it’s mid-summer for a few days before settling back to the seasonal norm of ‘slightly disappointing’.

There are probably 250 wild and not so wild plants in my urban repertoire, it may be more, I’ve never properly counted. Add to that at least the same amount from the hedgerows and the coast, plus numerous edible seaweeds and mushrooms. The list is enormous and the culinary possibilities are endless, so why should I find myself, at such a fertile point in the year and, unusually for me, with time on my hands, struggling to think of what turn my wild food journey should take next? I really have no idea. Perhaps the luxury of having time to think and the sheer abundance of what was available was all a bit too much, when most of my decisions, recipes and ideas are made, very much, ‘on the hoof ’. As I often do, I was picking a wild salad, wandering and selecting only the most tempting- looking greens, mulling over ideas but finding no real inspiration, until I randomly wondered if I could batter and deep-fry everything I had collected and how it would turn out. Pretty horrid, was the conclusion I reached, but now my brain was ticking and a nearby oak tree was calling to me. Eureka! Leaf crisps! Why had I never made these before?

Deep-fried leaf crisps with chilli and salt

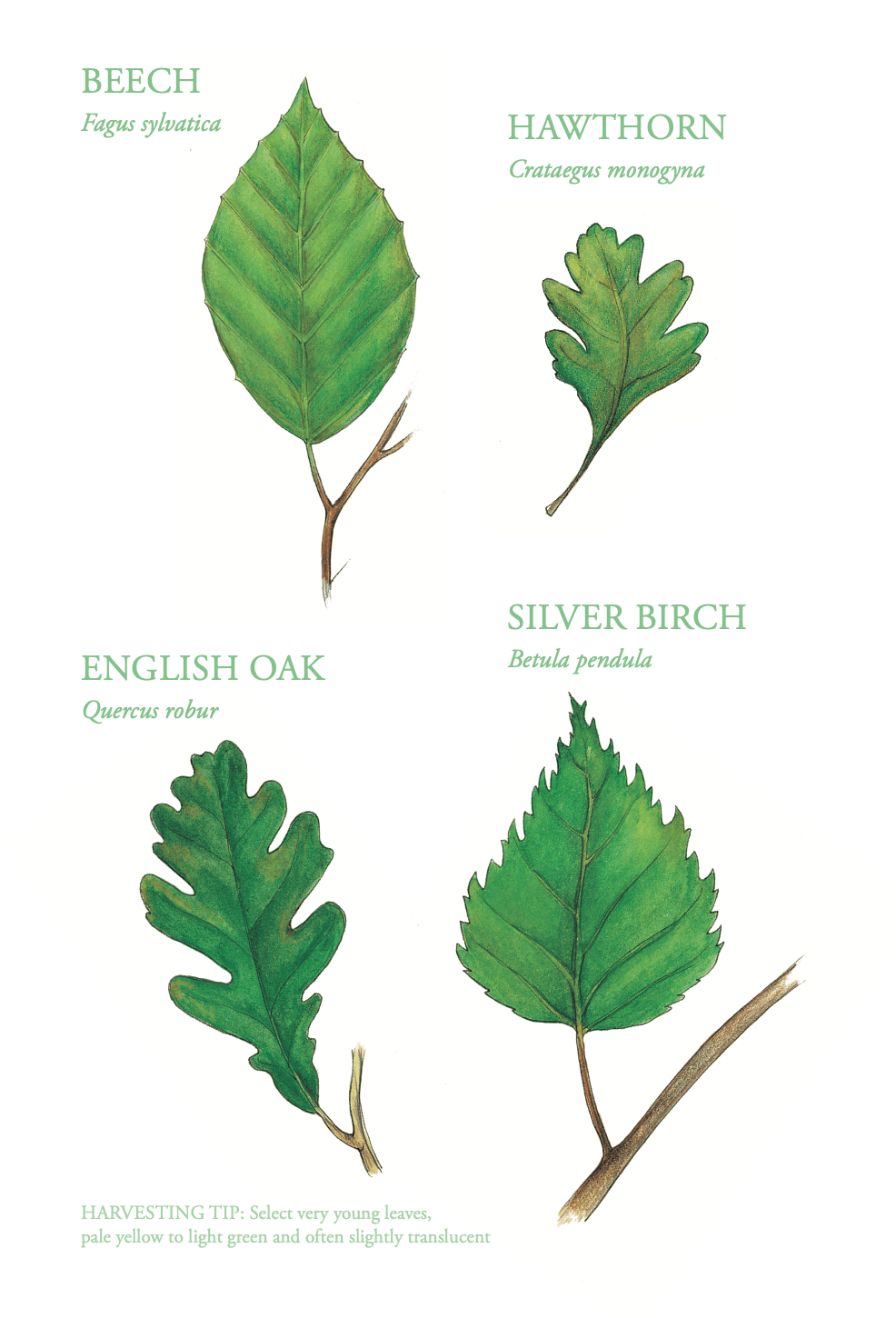

Young birch, beech and oak leaves, oil, salt, chilli powder

I say ‘deep’, but the method I adopted was a halfway house between deep- and shallow-frying, using a small saucepan and a few centimetres of oil, the same way I have always cooked seaweed. Having dry-fried numerous wild greens in the past, usually to make savoury sprinkles to add to my food, it’s bizarre that this penny had never dropped before. I’d collected a few varieties of tree leaves that I knew to be edible, or at least to not be toxic (so no trying this with the needles of the poisonous yew tree), including birch, beech, oak, hawthorn and linden, and experimented with each, getting varying results. The hawthorn were too tough and a little bitter, but this is a tasty leaf earlier in the year so I put this down to my poor timing, one to come back to. The linden was a disaster, as I expected, due to the high levels of mucilage, the substance that gives okra its signature sliminess – to say the least, they did not turn out well. The top three were the birch and beech, both of which have tender and opaque leaves at this time of year, and most surprisingly the oak. oak trees contain high levels of tannin, also found to a lesser degree in red wine and black tea, a preservative with a bitter taste, normally far too drying for the human palate. Acorns require soaking in numerous changes of water before enough of their tannins have dispersed to make them usable as a food, after which they produce an excellent and versatile flour, a truly under-utilized wild resource. My oak leaves were very young, pale green and, as such, much less bitter than they would become later in the year. Even uncooked they tasted oK, but once they had spent 10–20 seconds in the pan, then were drained on kitchen paper and sprinkled with salt and a hint of chilli powder, they were simply delicious and looked stunning with their classic wavy edge.

8th May. Looking for new locations in the south of the city

Organising urban foraging events is an excellent excuse to spend time in the capital’s parks and green spaces, and under the vague guise of work I have visited more of them than anyone I know. Being slightly north-of-the-city-centric, I am often asked to run more walks ‘south of the river’, the city’s physical and imaginary divide which seems to prevent even the most rational or socially mobile from crossing it. But today I made the transition without incident and spent the afternoon exploring the hidden wonders of Peckham, an astonishing little borough, counting twenty-three public green spaces in under two miles between Peckham Rye station and Burgess Park to the north. Like London in microcosm, it’s just so much greener than we imagine it to be. En route, I collected random ingredients, the way you might from a big food shop, but without any specific recipe in mind, only realizing later that I had subconsciously assembled a delicious simple salad and a wonderfully calmative tea to drink after.

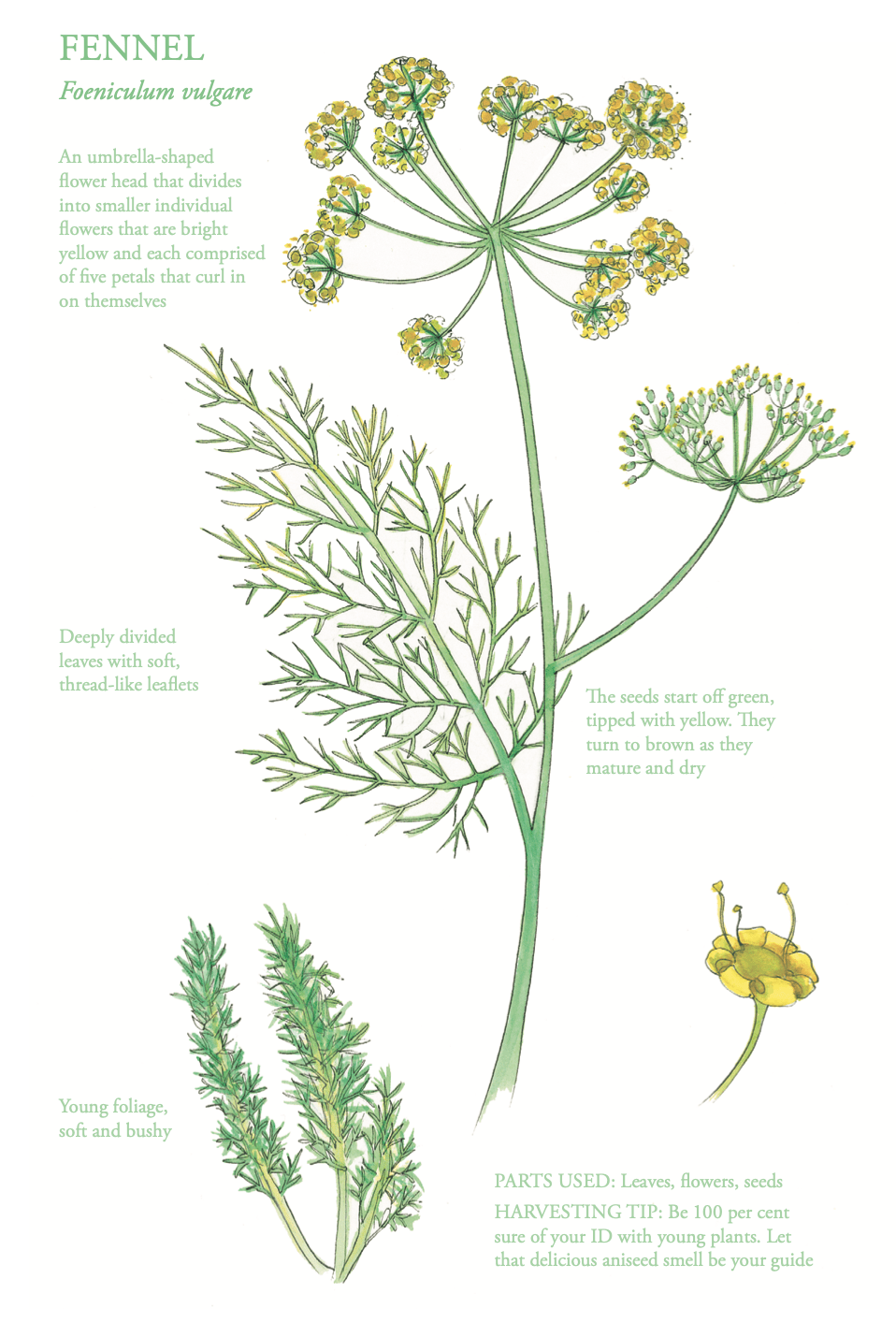

Lime leaf and ox-eye daisy has to be my favourite spring salad and usually I keep it to just these two ingredients with a splash of rose hip vinegar. Today, however, I also had fennel and yarrow in my bag; with their feathery foliage, both were at their absolute best in terms of sweetness of flavour and softness of texture. Fennel is perhaps the most scarce of these four in the city, but the ox-eye daisy is very common, and although in urban areas I tend to find its cultivated versions, they’re usually as tasty as its wild relatives, with delicious fruity leaves and yummy-scented flowers. Look out for great big daisies about 2 to 3 feet high with yellow and white flowers (but don’t eat any with entirely yellow flowers, they will be poisonous lookalike ragwort).

The lime leaves I collected are the heart-shaped foliage of the common lime or linden tree, found in abundance in every London park, with numerous medicinal properties attributed to both the leaves and flowers. The blossoms are used to make calmative tea, a treatment for stress and mild anxiety, while the leaves contain mucilage, a slimy substance that amongst other things helps suppress the cough reflex, so makes its way into home-made and commercially produced cough mixtures.

I picked young, slightly translucent new-growth leaves, munching a few of the bigger ones, too, selecting them from a height that even the most enthusiastic dog could not manage to wee on. The blossoms, not out yet, have the wonderful taste of honeydew melon; dried, they make one of the best-tasting of all the herbal teas.

A salad with lime leaves, yarrow, fennel and ox-eye daisy

Let’s be honest, generally when a book describes a plant’s best use as ‘making a great tea’, it means it’s rather dull and has no other merit. Not so for yarrow and fennel, two amazing-tasting herbs, packed with flavour and numerous medicinal and culinary attributes. Yarrow stimulates the appetite and aids digestion and I like to chew it when I have a sore throat. As a novice herbalist I use it for any and all ailments and in the kitchen as a salad, a cooked green veg and as a dried herb slightly similar to sage.

Fennel is one of nature’s best calmatives as well as containing anethole, a powerful aromatic compound also found in camphor and anise, antimicrobial and anti-fungal. Both plants are diuretic, so help to cleanse and purify the body, which is ideal for us city- dwellers. Combined, they make my favourite of all the herbal teas and are both easy to ID: mature fennel with its tall bluish stems, yellow umbrella flowers and distinctive sweet smell and yarrow with its low clumps of feathery leaves. Even so, one is a member of the Carrot family and the other looks like it should be; as such I would recommend you initially get to know these two plants with someone knowledgeable rather than just using an ID book.

Lime leaves (and blossom), yarrow leaves, fennel leaves, ox-eye daisy, sweet vinegar or olive oil, lemon juice and salt (optional)

Rinse, dry and combine the leaves of all four plants, the flowers of the ox-eye daisy, and the lime blossoms, too, if you have them. Add a small splash of sweet vinegar but don’t overpower these already wonderful flavours . . . Failing that, just use some olive oil and either a small splash of lemon juice or some salt, or both.

While we’re on the subject of fennel, it’s worth looking at a few of the other culinary uses of this wonderfully aromatic wild food. Any and all fish dishes can benefit from the herby sweetness this plant has to offer – fish cakes become elevated to a new level, baked trout takes on a more complex dimension and salmon cured with fennel stems, citrus fruits, coriander and black pepper knocks spots off your plain old smoked salmon. American foraging guru Green Deane recommends making a hearty pasta with penne, rigatoni, spicy Italian sausages and fennel stems while, closer to home, Devon’s foremost authority on wild food, Robin Harford, suggests making a sweet seaside pickle using chopped fennel sprigs and marsh samphire. The possibilities are basically endless . . .

15th May. Clissold Park, Stoke Newington

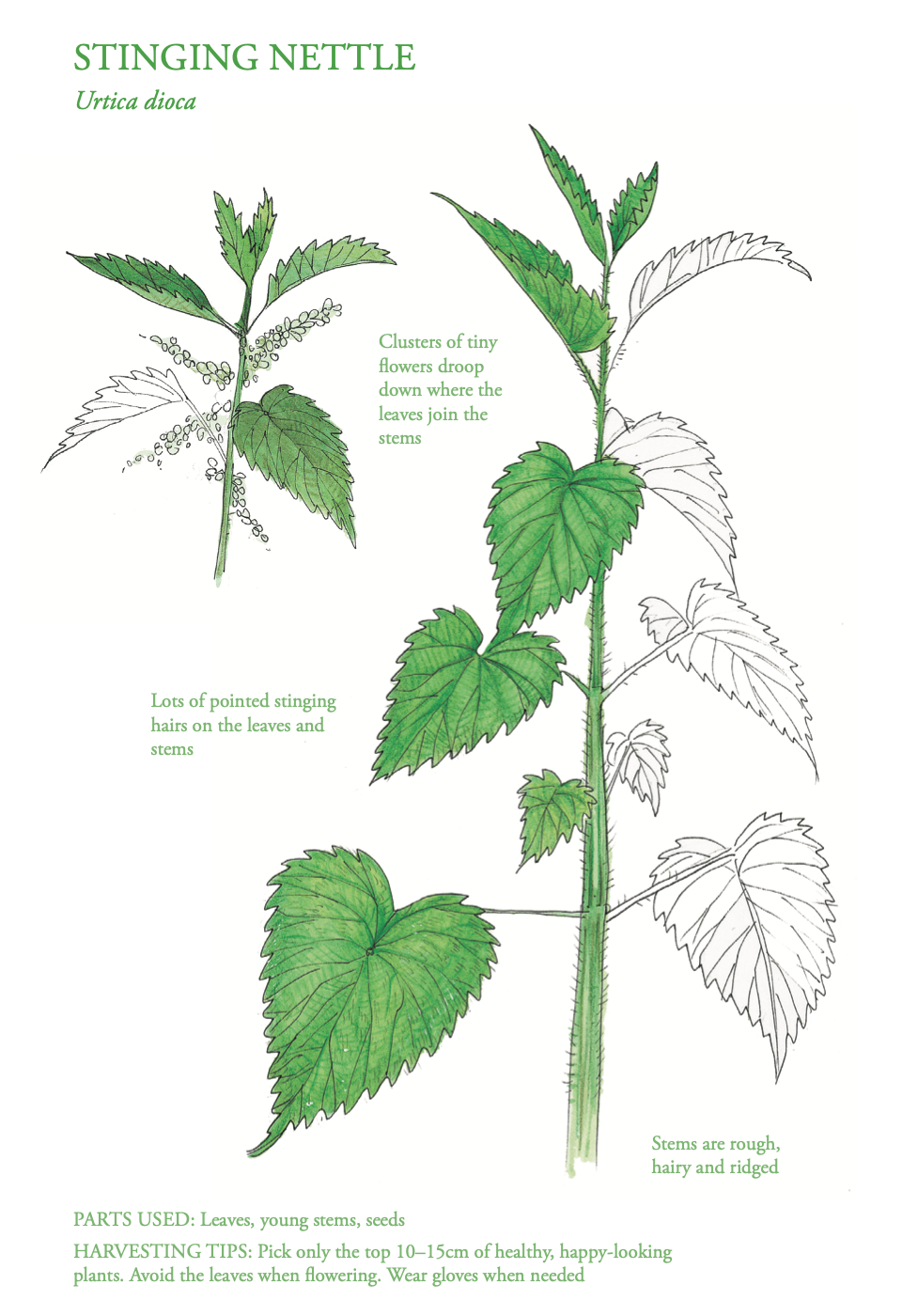

on this sunny May afternoon, armed with a big cloth bag, kitchen scissors and a pair of bright yellow rubber gloves, I headed for my favourite nettle bed (yes, I actually have a favourite patch of stingers),

an almost endless sea of these delicious wild greens. At this time of year there’s plenty of new growth coming through which I can use for making everything from nettle tempura (page 111), to a bright green protein- rich soup (page 104) or a spicy nettle aloo (page 137). But right now, it’s time for nettle beer. This always sounded to me like a nasty concoction my dad might have forced upon us in the 1970s, a horrific hippy brew, low on taste and high on gas. How wrong I was: ready to consume in just over a week from picking, this amazing drink tastes like a cross between a wonderful rustic cider and an old-style ale or sweet wine.

To pick nettle tops, that’s the upper 6–8 inches at this time of year, I usually use what I call the asparagus method, snapping the stem at the point at which it yields easily, moving up to the next leaf node and trying again if it doesn’t, avoiding anything that looks damaged or dull, just collecting vibrant, healthy-looking leaves. For nettle beer I’m a bit less choosy and find it quicker and easier to just cut them off. So absorbing was the simplistic pastime of nettle collecting that I forgot quite how bizarre I must have looked as I stepped out of the undergrowth and back onto the path, frightening a group of joggers. Carrying a huge cloth bag slung around my neck and my bright yellow rubber hands brandishing a large pair of scissors . . . I was probably grinning, too! I apologized, explained myself and left the park quickly before the armed response unit turned up, or even worse the local residents association.

Nettles are a great ‘cut and come again’ plant, so if your local patch gets too tall, making the nettle tips too robust (and full of gritty crystals), you can cut them down and come back for the delicious new growth a few weeks later.

Nettle beer

This is the perfect drink for students, or anyone who’s on a budget. As beers go it’s very gentle but I’m never sure exactly how alcoholic it is (roughly 3 per cent ABV, I reckon); I have a hydrometer for measuring such things but rarely bother with anything so specific in any of my recipes.

Nettle tops, 500g white or brown sugar, 25g cream of tartar, 8g brewer’s yeast

Take about fifty nettle tops (roughly the top 15–20cm of each should fill a carrier bag), picked as described above, wash them, still with your rubber gloves on, before adding to 6 litres of water (usually in two pans unless you have one huge one). Bring to the boil and simmer for 15–20 minutes before removing the nettles (eat them as a cooked veg or use to make a year’s supply of nettle pesto) and adding the sugar and cream of tartar powder. Stir until the sugar dissolves and let the liquid cool to tepid before mixing in the brewer’s yeast. Then leave, in a sterilized bucket with muslin over the top, for a few days before siphoning into sterilized bottles. If you have not done any siphoning before, this is the fun bit and just requires a length of clean plastic tube (you’ll find plenty of demos on the internet but you can ignore most of what they say, it’s really very simple). I usually leave my beer for five days but I have read of people leaving it up to two weeks. You need to let the first fermentation stage do its thing or your bottles will explode in dramatic fashion.

If you do fancy experimenting then try adding lots of grated fresh ginger to make a more spicy drink. This recipe makes about a dozen normal-sized bottles. To work out how alcoholic it is you could try drinking it all in one go and then compare this experience to drinking twelve shop-bought beers. Take notes, though, this is serious scientific research!

25th May. The River Test, Hampshire

As summer approaches, many of the spring salads begin to turn woody and a little too bitter, while the autumn fruits and fungi are still a long way off. Where then should we head for the best foraging opportunities? Ideally the most mixed environment possible, which makes an estuary an excellent place to visit; the land meets the sea meets the river and with them a huge variety of seaweeds and sea beets, salt-marsh plants like samphire and purslane, and river’s-edge plants like meadowsweet and comfrey. Although I didn’t quite make it to the coast today, I did manage to subvert a trip to visit the in-laws, turning it into a wild food walk, ambling along the riverbank, looking at the wildlife and picking a few delicious edible plants to cook up later. When I’m back in the city, I crave the pace that a riverside walk imposes on me, the proximity to the water and its gentle movement, time slowing down a little and the family getting the chance to be just that, to chat about nothing in particular and enjoy the balance that comes from having all age groups present. Some events are instantly frozen in time, memories even before they’ve finished happening; with a saturated colour palette of low sunlight, reflections kicking off rippling water and the gentle shush of a breeze as it teased the tops of the reeds, today’s walk was exactly this. But most vivid of all, many years from now I will remember this day, based entirely on its smell, the strong and sweet odour of mint, with a waft of turpentine thrown in – this is the smell of water mint.

Water mint ice cream

On its own, this is a great herb to serve with freshwater fish, especially trout, which I like to bake in foil, stuffed with water mint and ground ivy (which prefers to grow on riverside paths rather than the actual banks). How do you know it’s water mint? It grows by or in the water and it looks and smells like mint, actually quite similar to peppermint in both appearance and fragrance.

20 sprigs of mint, 5 tbsp caster sugar, 375g crème fraiche, 3 egg whites, green food colouring (optional)

I found this recipe in a lovely book by Adele Nozedar called The Hedgerow Handbook, packed with simple and tasty ideas and beautiful illustrations.

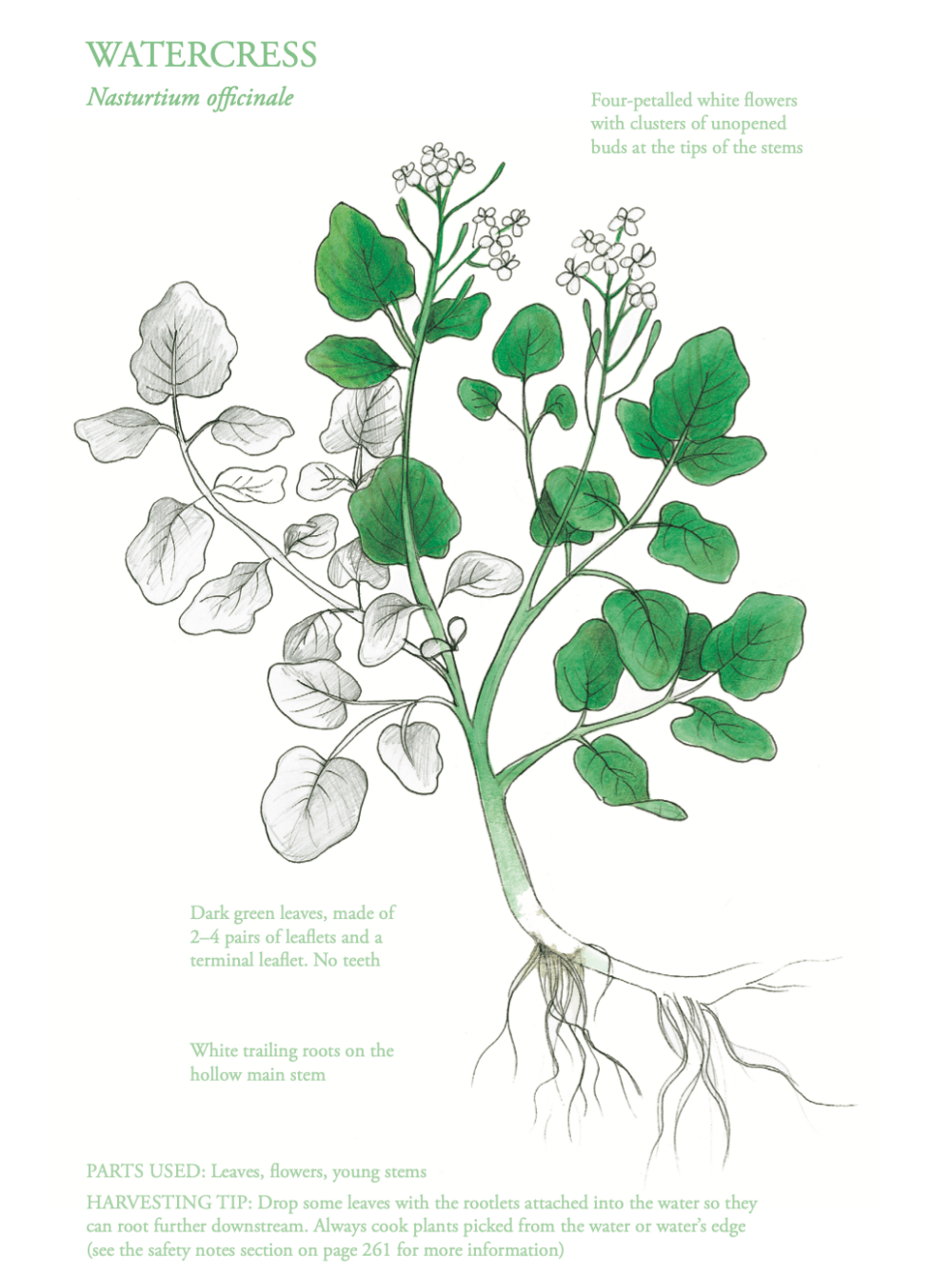

Wash the sprigs of mint thoroughly then blanch in boiling water for a few seconds. As with any water’s-edge plant, this step is a vital safety measure and will kill any parasites present (more information in the watercress section on page 104 and the chapter on safety on page 261). Now whizz the mint in a blender with the caster sugar, transfer to a bowl and stir in the crème fraiche. In a separate, clean bowl, whisk the egg whites to ‘soft peaks’ (this bit takes bloody ages) and fold them carefully into the mixture. I also added a bit of green food colouring. Transfer the mixture to a plastic container and put this into the freezer, stirring every half hour or so with a fork, to avoid it crystallizing (unless you’re lucky enough to own an ice-cream maker which can do this for you). obviously this recipe works with other types of mint, too.

26th May. Reluctantly returning to the city

Don’t get me wrong, I love this city, but sitting in a traffic jam for three hours in order to get back to it is not my idea of fun. Fortunately, Ellie has the ability to be rational about these things; when all I see is a national conspiracy designed with the sole purpose of giving me back ache, she perceives an opportunity and a chance to explore a bit of the countryside that we usually only whizz straight past. I’m not entirely sure where we ended up, but I was delighted to be there, swapping the frustrations of stationary vehicles for the delights of rolling fields, flower meadows and another riverbank, our second in as many days. Time spent by the river always reminds me of being on holiday as a child, trying but failing to catch a trout and always ending up waist-deep in the water. Today I had no fishing rod with me and I saw no fish, but the water quality was good, as indicated by the land around it supporting

a diverse range of wild flowers and, more importantly, huge floating pontoons of one of my favourite wild foods, watercress. This delicious member of the cabbage family is available in various stages of growth almost all year round – I have even harvested some when there was snow on the ground. Thankfully, today was hot and sunny, becoming a perfect late spring day the second we left the rest of humanity behind. We sat on the grass and ate a makeshift picnic, more motorway services than wild food buffet, but old habits die hard and ten minutes later, having successfully gathered a huge bag of watercress, I was up to my waist in the river, sodden but happy. We sat in the sun by the river while we waited for the traffic to die down and for my clothes to dry out.