1st October. At home in the north of the city

I’d driven back from the woods (a loose title I give to most of Hampshire) the night before, having run two enormously enjoyable mushroom-hunting walks, and for the first time in a good nine months my fridge was half full with delicious and beautiful wild fungi. I have to agree with Italian chef and mushroom obsessive Antonio Carluccio, who evocatively describes mushroom foraging as ‘the quiet hunt’. I always find this calming and absorbing multisensory treasure hunt, set in an area of stunning ancient woodland, the perfect antidote to city life. I don’t pick any urban mushrooms these days, not that I ever collected many, but having researched the topic at length and studied the ways in which mushroom mycelium is so wonderfully adept at absorbing any and all toxicity that it encounters, if I want to indulge my autumn urges, I get well away from the city. My advice to any novice fungi fancier, go hunting with someone you have 100 per cent faith in and who has a proven track record . . . small mistakes can lead to horrific results and I never, ever, take my ego out with me when I go foraging. If I can’t ID what I come across that’s absolutely fine, so long as I have no intention of eating it. And in exactly this way, novice foragers can stay safe; if the ultimate destination of a few wild mushrooms is the compost heap not the dinner table, nobody will get poisoned. I know mushrooms are one of the things people are most excited about finding, so I have included recipes for five of my favourite species, all of which are easy to ID, but I can’t overstress the need to be cautious and careful.

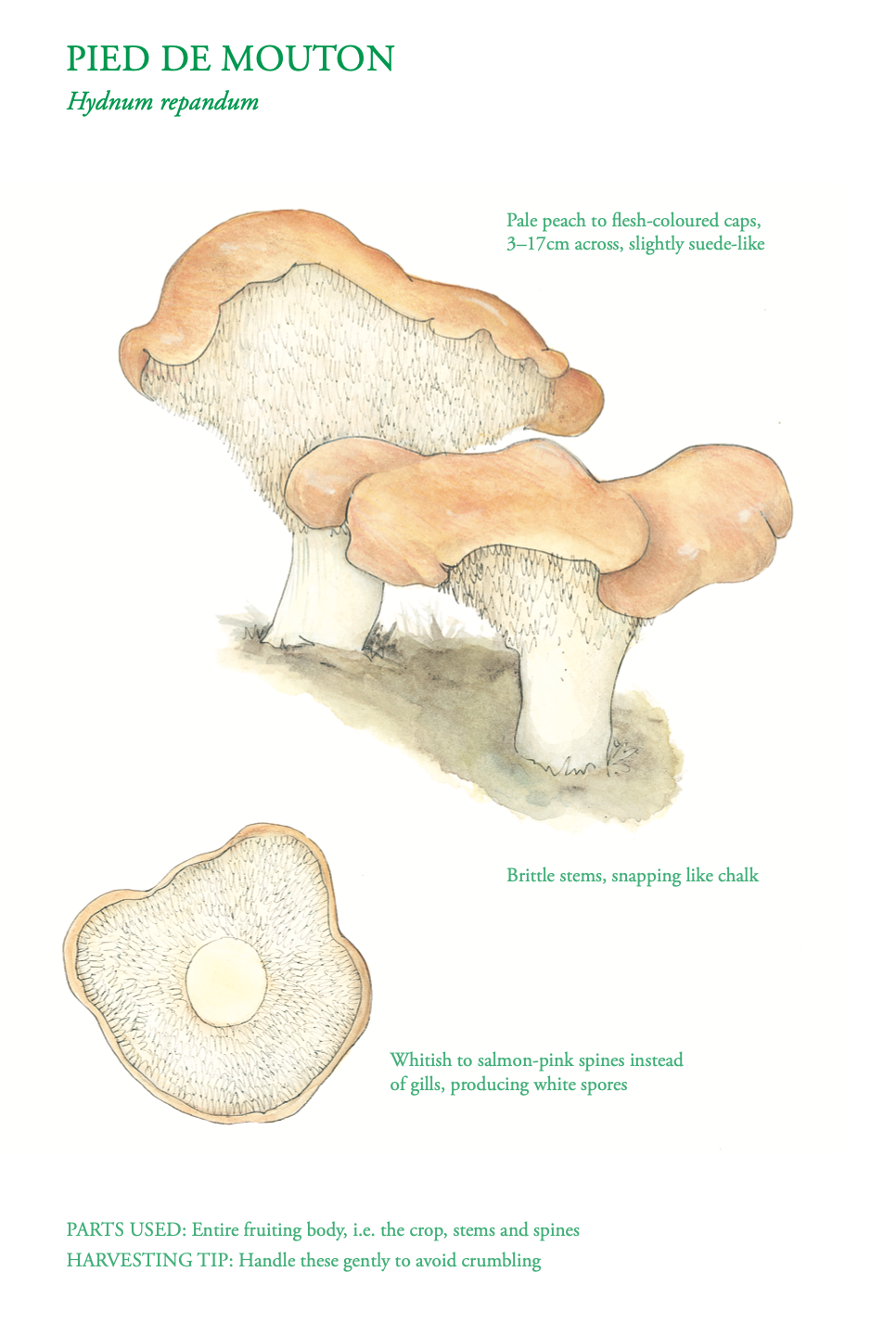

So, what was in my basket or, more specifically, my fridge? A fine selection of shapes, sizes, colours and smells; mushrooms with some wonderful common names like horn of plenty, pied de mouton, charcoal burner, cauliflower fungus, amethyst deceiver and slippery Jack! A fridge like this, full of autumn fungi, really makes me smile, but it also makes me yearn for the woods, my happy place, they quite literally tug on my heart and beckon me to it. Even if I can’t get back there as soon as I’d like, at least I get to enjoy its amazing bounty.

Pan-fried wild mushroom risotto cakes

2–3 shallots, 2–3 garlic cloves, olive oil, butter, fresh herbs, 1kg assorted wild mushrooms, 250g risotto rice, 1 large glass of white wine, 850ml vegetable or chicken stock, salt and pepper

Makes 8 cakes

What’s that expression? ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,’ better still, steal it. Sorry, Garry, this is too good not to share.

Peel, finely chop and sweat down the shallots and garlic in olive oil and butter for 2 minutes, add the fresh herbs and the roughly chopped wild mushrooms. Cook for a further 2 minutes, then add the risotto rice, stirring it to soak up the delicious juices and oil. Add the wine and keep stirring until it evaporates, then a ladleful of warmed stock every couple of minutes or so as the risotto gets sticky. Keep stirring and after about 20 minutes stop adding stock (you need the risotto sticky to bind together). Stir in a large dollop of butter and season to taste.

Leave it to cool. Line a flat tray with greaseproof paper, place stainless- steel rings (about 8–10cm wide and 2.5cm or so deep) on the tray and pack tightly with the risotto mixture. Fill as many as you need before carefully removing the ring and setting the cakes in the fridge overnight.

Heat a large frying pan with olive oil and butter and add crushed garlic to flavour the oil before pan-frying your cakes until they are golden brown on both sides.

(Recipe courtesy of Garry Eveleigh, aka The Wild Cook.)

4th October. Inside the M25, but only just

Autumn makes my head spin; the wild world is in hyper-drive, and the extra warmth we get in such a big city adds an additional layer of not so seasonal plant growth into the mix. Mushrooms were popping up everywhere, the fruit trees were heavily laden and, in my neighbourhood, all the springtime salad plants were having a second go, putting up lovely fresh growth and some even flowering, again! Today, realizing that I’d forgotten to make my annual batch of elderberry and clove cordial, and that the city trees had pretty much dropped all their fruit, I headed off in the car, figuring the slightly colder climates out of town would give me the chance to pick from trees a few weeks behind my local ones. I drove just ten miles, almost to my mum’s house, before I was rewarded by a line of elder trees, laden with deep purple berries and apparently a good month behind the ones on my doorstep. The difference in temperature may have only been a degree or two but that was all it took. I set to work, armed with my big cloth bag and patented berry hook, a sturdy willow branch that divides to form a large hook at one end and fitted with a long loop of string at the other. I hooked one of the boughs, carefully pulling it down before sticking my foot in the loop of string to keep the stick and, more importantly, the fruit, where I wanted it, and giving me two free hands to pick with. Snapping off each spray of berries and bagging them is the easiest and most effective way to gather large amounts of these tiny fruit.

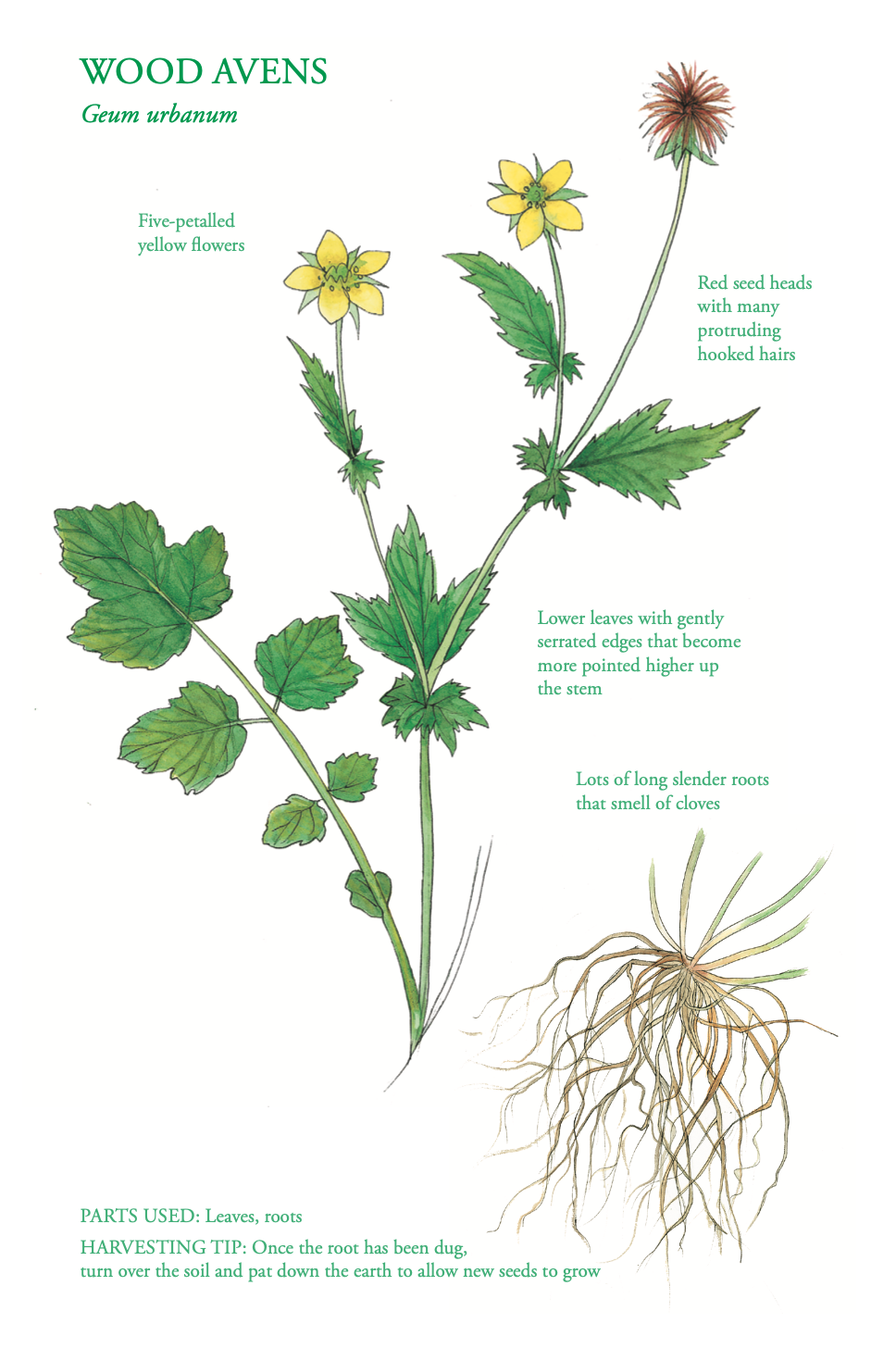

Normally I’d be happy to use conventional cloves as my other main ingredient, but presented with the low green growth of a common plant called wood avens, it was obvious that I could use it, not least of all due to its other common name, clove root. A member of the Rose family, resembling a strawberry leaf, more rounded and far hairier, it’s the roots, not the upper parts of the plant, that have a wonderful nutmeg, cinnamon and clove flavour. So common is this unassuming little plant that, rather than dig them up on the spot (you need the landowner’s permission to do so), I just headed home and dug up a few in my own back garden.

Elderberry and clove root cordial

1–2kg elderberries, 500g sugar per 1 litre of liquid, cloves and wild clove roots

I say it’s a cordial but it tastes so good that I have never managed to dilute it; instead I drink a neat shot every day throughout the winter. It’s not often that pharmaceutical and herbal medicine are in complete agreement but they are when it comes to elderberries. Clinically proven to combat colds, not only a great natural antiviral but also an anti-inflammatory, a diuretic and a decongestant, in other words pretty much everything you need to stay healthy in wintertime. Medicinal properties aside, the joy of knocking back such a tasty treat every day is a fabulous tonic in itself.

Gather a basket of elderberry sprays (at least a kilo, ideally two) and, at home, remove the berries with a fork, dropping them into lots of cold water. Most red or green berries or any shrivelled ones will float, making them easy to skim off, while the ripe ones will sink. Simmer them for 20 minutes in enough water to cover them, plus another few centimetres for good measure. Strain the lot through muslin and wring it out to get as much juice as possible. Discard the fruit before adding about 500g sugar for every litre of liquid, bringing it to the boil and simmering for another few minutes. Bottle in sterilized bottles, adding 15–20 shop- bought cloves per bottle but preferably a mix of these and wild clove root, washed, dried and snapped from the rest of the plant. When digging roots it pays to leave the top of the plant in place to help with identification, only removing it at the last minute. It’s the finer lower fronds of this root that contain the flavour, not the tough woody bit that joins the foliage. Give one a nibble to get an idea of the taste – for the experience as much as to judge how much to add. Ready in a couple of weeks but it gets better and better as time passes and the cloves and clove root infuse. Keep some in the fridge and freeze the rest.

As a footnote, when I asked my friend Robin Harford if I could use and adapt this recipe, he responded sagely, ‘of course you can, we’re all standing on the shoulders of giants.’

6th October. A secret location on the border of Dorset and Hampshire

I’m always excited when I cross that imaginary divide that separates the city from the countryside, and today, driving south to run another two mushroom forays, I had no one to keep me in check. The three-hour journey became punctuated with numerous stoppages, woodland car parks and random detours, finally arriving six hours after departing. Sometimes Ellie suggests we go for a walk, then she’ll look me in the eye and explain that this activity involves walking, not just remaining

in roughly one spot collecting wild plants or mushrooms. I try to keep moving, I really do, but it’s just so hard, especially when my inner child is finally let loose in the seasonal sweetshop of an autumnal woodland. En route, a friend rang, a fellow forager and mushroom obsessive, who’s lucky enough to live in an area of gorgeous mature woodland. ‘I’m just off to check my secret trompette patch, do you want to join me?’ This may not sound that exciting to the uninitiated but for me it would be right up there with offers like ‘Would you like to visit my secret diamond mine?’ or ‘The sheikh would like to invite you to spend some time in his harem.’

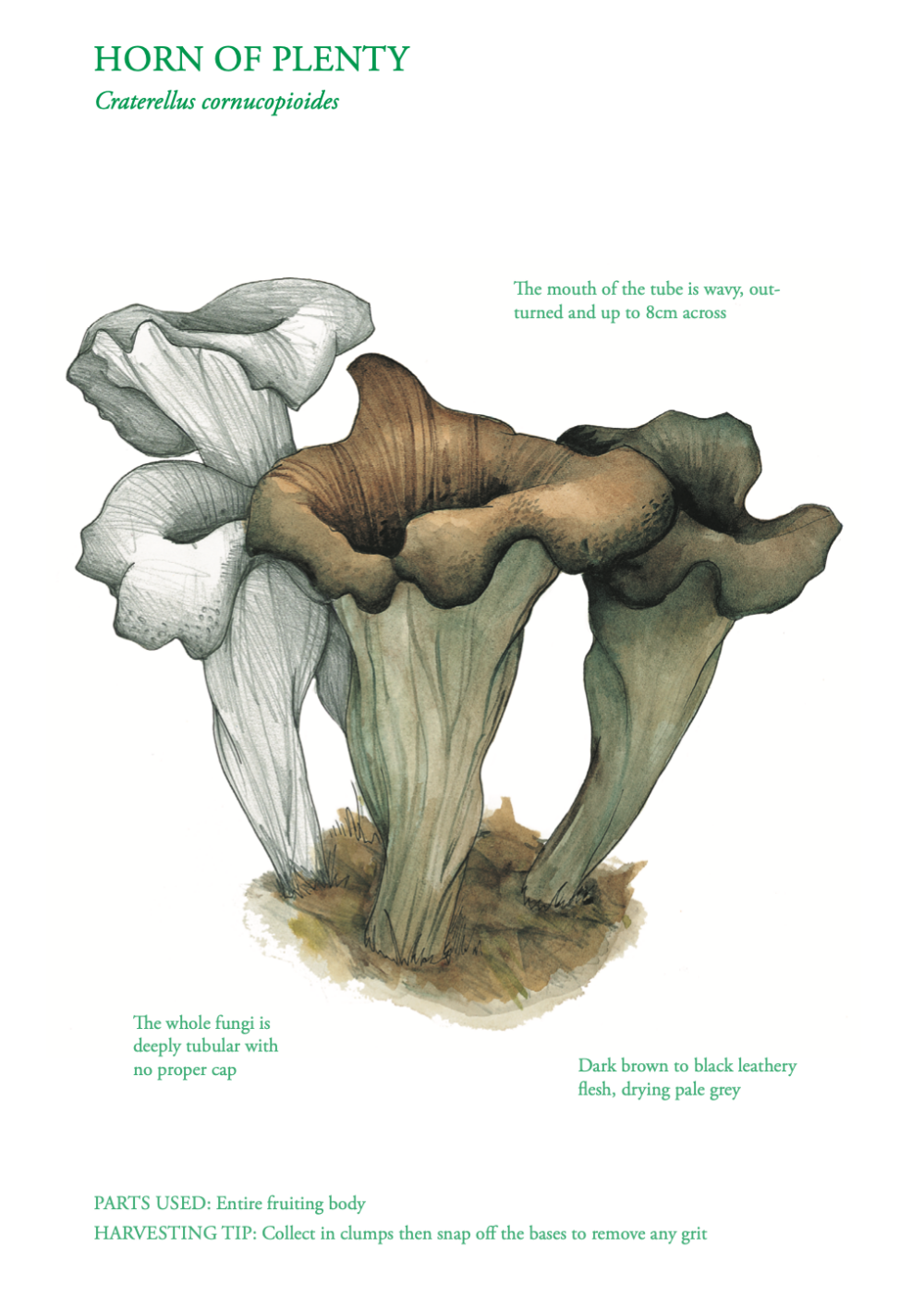

Needless to say, I accepted and half an hour later we were both standing outside a relatively famous, very large country pub, me expecting to be blindfolded and driven to this most prized of hidden places. Instead, I followed my friend as we crossed the road, taking literally two steps into the woods before he pointed, not off into the distance but just down at our feet. Trompette de la mort, otherwise known as horn of plenty, one of the most prized gourmet wild foods, with a heady truffle smell and shaped, as you’d expect from their common name, like very dark trumpets. I knelt down to pick the small group of perfectly formed, 4-inch-high horns at my feet and only then, once at ground level, did I really see what he had brought me here for . . . oh my god . . . double take, wipes eyes . . . looks again. Here, in full view of the pub, the road and the pavement, was an endless sea of black, the forest floor gently sloping away for at least a quarter of a mile and everywhere I looked, delicious, extremely sought-after, free food. I’m not a commercial forager and other than for personal use, collecting wild mushrooms in this part of the country is not permitted, certainly not in bulk. Regardless of this I did the maths and realized I was looking at thousands of pounds worth of fungi, at least 200 kilos, and that was what I could see without walking any further. For once, I may have just slightly exceeded the recommended daily picking limit of 1.5kg per person, aware that a week or two later, although easily discoverable by anyone who wanted to pick them, every single mushroom here would have collapsed and rotted back into the soil. What a waste.

Spicy wild mushroom ketchup

I’d already made a trompette omelette, a trompette soup and had trompette on toast with, or for, every meal for the last two days. Oh, and I’d also soaked a couple of handfuls in a good-quality vodka with some red chilli, producing the most wonderful base for a Bloody Mary. Under normal circumstances, I would make this recipe with a less sought-after fungi, but when faced with a glut of these amazing black horns I couldn’t help myself.

1kg wild mushrooms, 4 bay leaves, 5 or 6 cloves, 11⁄2 tbsp salt, 1 tbsp dried porcini powder or a few dried porcini, 1⁄2 tsp ground ginger, 1⁄4 tsp grated nutmeg, 1⁄4 tsp allspice, 1 star anise, 1⁄2 onion, 1 garlic clove, 375ml white wine vinegar, 1 small glass of sweet sherry (optional), black pepper

Mushroom ketchup is a traditional recipe and a great way of using and preserving your favourite fungi. Although the more acceptably produced version is very thin, more similar to a Worcestershire sauce, my creation was much thicker, very spicy and like a dark grey tomato ketchup.

First take the mushrooms, shop-bought if you have no choice, rinse if needed (not usually advised but sometimes necessary with trompette), chop and put them in a large bowl. Add the bay leaves and cloves and mix in the salt before leaving in the fridge for 24 hours.

Remove the cloves and bay leaves, then carefully remove the mushrooms and transfer to a blender, gently pouring the liquid from the bowl over them but making sure there is no grit at the bottom. Blend, then put the mixture in a big saucepan and add about 650ml water and, if you have it, the dried porcini powder – otherwise a few dried porcini mushrooms will do. Also add the ginger, nutmeg, allspice, star anise, the finely chopped onion and garlic, lots of black pepper and the wine vinegar. You can also add a small glass of sweet sherry, but it’s not vital.

Bring the whole lot to the boil and simmer gently for an hour, stirring often. Wonderful smells will fill your kitchen until it is time to pass the whole mixture through a sieve to remove any lumps and then bottle into sterilized bottles or jars. I never make the same thing twice so I suggest you play with quantities; you can easily produce a much thinner version with half the amount of mushrooms or more liquid. Keeps for a few months in the fridge.

10th October. Somewhere in the shadow of Arsenal Football Stadium

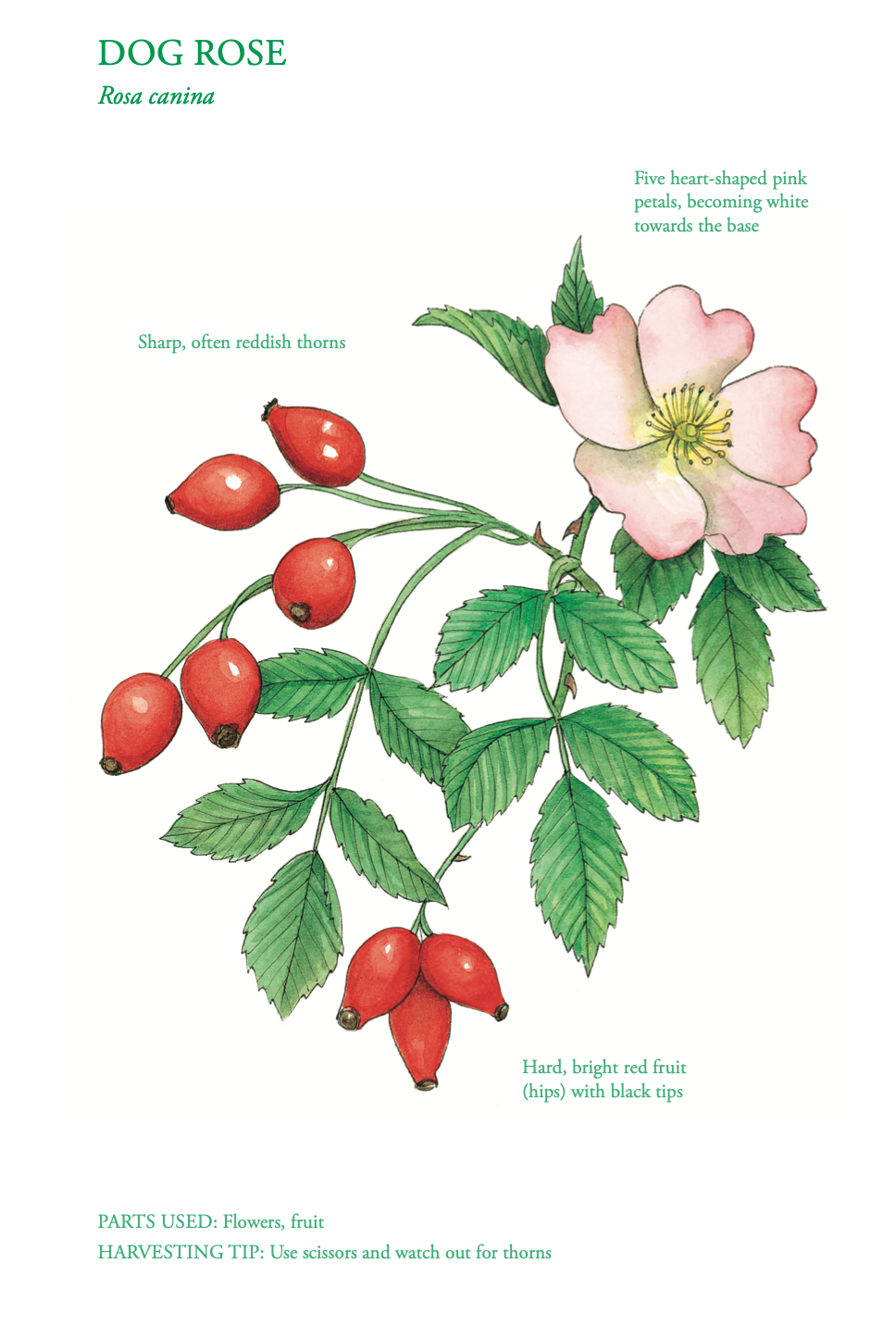

It’s a tricky time of year for me; the city dweller wants the dry weather to go on forever, while the fungi hunter wants the rain to come and help the mushroom season along. Where I end up foraging is very often in the hands of the gods, so I find it best to just concentrate on the abundance of wild and not so wild fruit that the summer has delivered, and if the weather does turn, then off to the woods I go. Last year was quite literally a wash-out, but this year’s alternate periods of hot sun and heavy rain had sent the fruit trees and bushes into overdrive. Like so many of London’s best foraging areas, this little gem of a park is tucked away, a magical doorway leads from the street, straight into this wild Narnia. Everything on my picking list was here . . . crab apples, bright orange rowanberries, pears, medlars, hawthorn berries, sloes and blackberries. But best of all, a hedge about 200 metres long, festooned with 2cm scarlet ovals, wild rose hips – dog rose to be specific. I never tire of expounding the health virtues of these amazing fruits. Weight for weight, rose hips contain twenty times the vitamin C of oranges, masses of pectin (commonly used in throat lozenges), high levels of antioxidants, beta-carotene, vitamin B and essential fatty acids, and let’s not forget the fact that they taste fantastic.

Rose hips freeze really well and I use them for syrups, sauces and to give sweetness to numerous recipes. I collected about a kilo in under half an hour, a big cotton beach bag round my neck, leaving both hands free to pick as I moved sideways along the hedge like a cross between a crab and a space invader, grinning like an idiot and humming like a bumblebee.

Traditional wild rose vinegar

Rose hips, white wine vinegar or white balsamic vinegar, sugar (optional)

Due to their impressive size, I prefer to pick Japanese rose hips (not a native but thoroughly naturalized) but any variety, wild or otherwise, will do perfectly well and different species will give varying flavours. Part of the joy of this recipe is in the presentation, so if you’d like to end up with bottles filled with rose hips you’ll need to use a variety that will make it past the bottle neck and dog rose are one of the most attractive in shape as well as colour.

Another of my recipes that’s hardly a recipe at all. Pick bright red hips, ripe but still firm, then top and tail them with a sharp knife before sticking lots of little holes in them with a pin. Be sure not to cause any damage that will let the little hairs from the centre escape. Alternatively, you can freeze and defrost the hips to soften them but I prefer the process of picking and pricking each one. Find an attractive clear glass bottle or jar, depending on the size of your fruit, fill it with hips, then fill the remaining space with white wine vinegar or, if you’re feeling lavish, white balsamic. For a sweeter version, heat the vinegar and add a heaped tablespoon or two of sugar to every 100ml of liquid, then leave it to cool before adding it to the hips. About 6–8 weeks later it’s ready to use, and in the meantime make sure you leave it sitting around where people can admire your creativity.

26th October. Richmond Park

Strange, but when out foraging in the city, Richmond Park is exactly

the sort of area I avoid, Hampstead Heath, too. It’s not that they aren’t wonderful places, amazing resources, especially for nature-starved urbanites, and terrific for learning about wild plants, but for me they’re just a bit too obvious. When I tell people what I do, how I spend large chunks of my time, these are the places that always get mentioned and although they do hold some wonderful foraging possibilities, I seem to prefer the surprises that less picturesque, less visually appealing spots have to offer. I was always a grubby child, hands in the dirt and staring at the ground, claiming that I was looking for treasure – apparently nothing has changed. Today I visited a relative of mine in Putney; once a towering figure of the music and entertainment industry, these days she prefers to stay home. We spent the morning drinking tea and looking at old photos of her with Lauren Bacall, Frank Sinatra, David Niven, Tom Jones and Shirley Bassey.

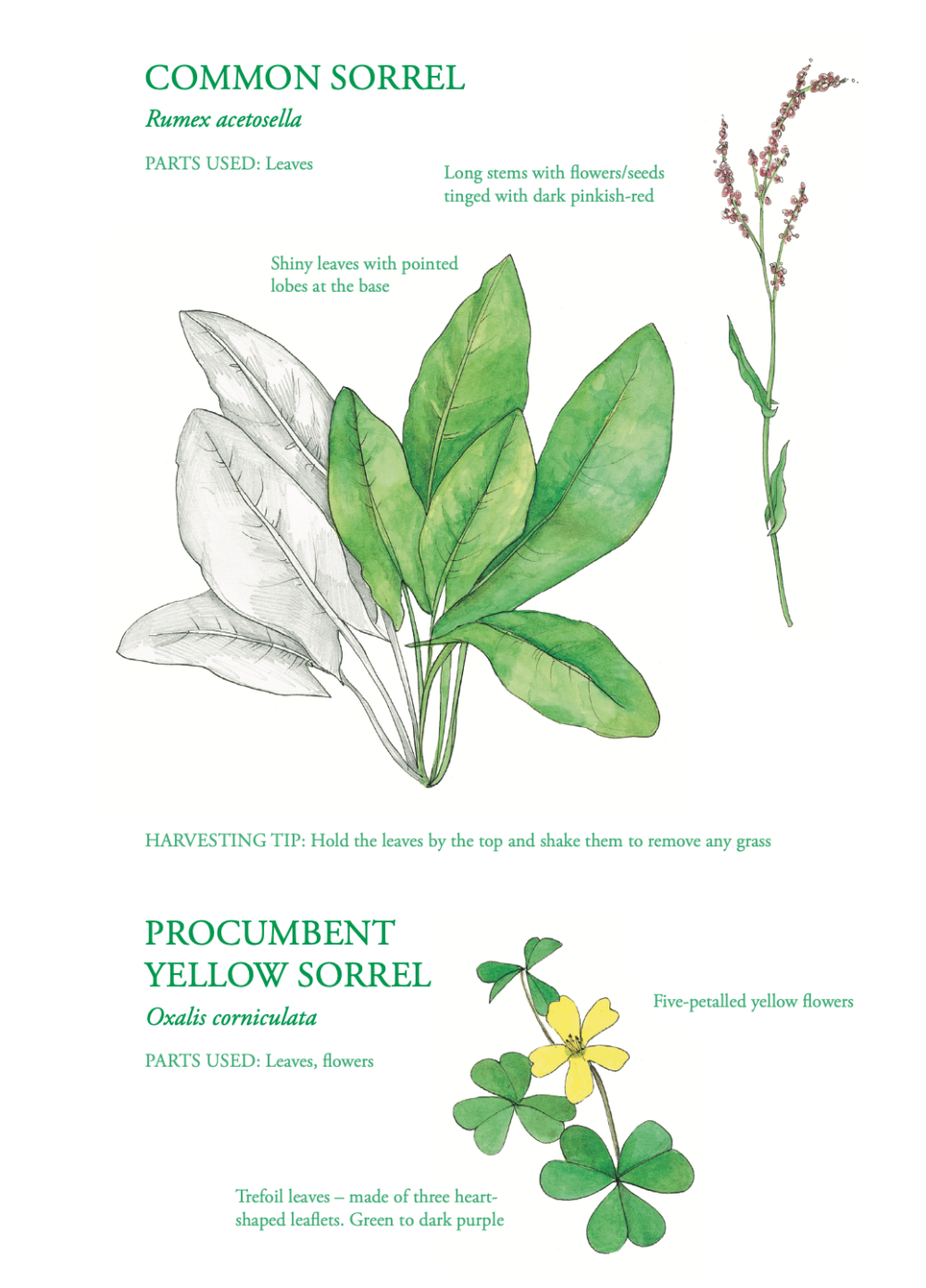

I actually don’t get over to this part of the city very often; despite its scale, Londoners are basically village dwellers and prefer to stay in their own little areas. So later on, it was a good chance for me to take a walk across Richmond Park and do some very nerdy mushroom spotting (as I have already mentioned, I don’t pick any city fungi). There was plenty to see as I walked through the long damp grass: brightly coloured wax cap mushrooms popping up everywhere, lurid shades of red, yellow and green; field blewits with fat white caps and bright purple stems; and even the odd parasol mushroom, huge and visible from a hundred yards away. Another question I often get asked is how often do I go foraging, the honest answer to which is, I’m always foraging, I never stop. Even if I’m not actually picking something, I’m taking in my surroundings, looking at what’s in season, what’s coming in, what’s going out, scoping out new areas and enjoying familiar ones. And so it was that I found myself on autopilot, gathering pocketfuls of delicious common sorrel leaves, crisp and bright green, with an intense lemon meets apple flavour. For safe identification or, more specifically, to distinguish it from a toxic plant called lords and ladies (Arum maculatum), make sure the two points that make up the bottom tips of the leaf are exactly that: points, tapering sharply, as if they have been cut with scissors, rather than gently rounded off. It’s amazing just how much foliage you can stuff into the pockets of a decent Parka, ironically the same style of coat I’d have been wearing as a treasure-hunting kid.

Sorrel stomp, aka zurkelstoemp

Last year I invented a cocktail with sorrel, pulverizing a bunch of its leaves with a similar amount of apple mint (any mint will do), then adding them to a third of a bottle of good-quality gin. There’s only one gin for me, and I’m not going to advertise but it contains twenty-two foraged ingredients and is made on Islay, in Scotland. Also into the gin went some dandelion flower syrup (sugar or honey will suffice), giving it some extra sweetness and a warm orange-yellow colour. We christened the new drink, naming it after my friend’s dog Moon, and hence the Moon Dog Martini was born.

Sorrel has multiple uses in the kitchen (tasting as it does, like lemon) and is obviously the perfect ingredient in any seafood dish. I’m not a fan of poached fish but it will certainly bring a zesty lift to some poached salmon, although I prefer mine pan-fried so the skin goes crispy, with the sorrel leaves served on the side. You could also try creamed sorrel with poached eggs or consider adding it to a traditional Turkish lentil soup or mixing into a pea and parmesan risotto. A final thought, common sorrel and the unrelated wood sorrel (often referred to as oxalis) are almost identical in taste and are interchangeable in culinary terms, although the latter looks more like a species of clover. If you find this growing in the city it is more than likely to be one of the various cultivated and feral varieties such as procumbent yellow sorrel.

Potatoes, bacon, sorrel, garlic

I’ve often considered the possibility that I actually prefer collecting books about wild plants more than collecting the plants themselves, but really one is an extension of the other, and both a bit compulsive. I’m never exactly sure how it happens, but sometimes I end up with three copies of the same book, so last year I asked people to send me their favourite springtime foraged recipes in exchange for a spare copy of Roger Phillips’s classic Wild Food. The winner was An Vrombaut, who sent me this delicious Belgian dish which literally means sorrel stomp.

A simple mix of broken-up pieces of cooked potato (it could be mashed but I plumped for boiled with the skins left on), chopped-up fried bacon and loads of fresh sorrel leaves mixed in, it’s a brilliant way to showcase the amazing zesty flavour of this plant. Some fried garlic found its way into mine, too. Wonderful, hearty, peasant food and with sorrel leaves available most of the year, it makes a terrific autumnal breakfast.