“the flavour of the plant is utterly irrelevant to the plant”

Let me start by summing-up foraging. It’s not just about identifying plants. Foraging is really about forming an intimate relationship with a plant and what that plant will do across the seasons: how it’s chemistry will change and the different flavours and, therefore, culinary, medicinal, booze-related possibilities it will offer you. Some plants start the year tasting amazing but finish the year tasting revolting. Some plants have one part that tastes amazing but the rest will be poisonous. Some plants have a tiny window of opportunity – what I term a “micro-season”. Some plants are just very contrary; for example, Mahonia, which is a kind of border plant or rather “barricade”, which has been used all over our parks. It produces little purple berries and in December, big, yellow towers of flowers that look a bit like fireworks shooting upwards. Now, if you pick the berries on the right day, they taste sweet; on another day they can taste like grapefruit. Pick them on another day and they can taste like s***. The window of opportunity in which to pick exactly at the right point is sometimes very small. Sometimes it’s two weeks and sometimes it can vary from plant to plant – whether that plant is in the sun/shade/pollinated/ill etc. Annoying? Not really. Obviously not great if you needed a particular ingredient that day – a bit like finding something you need for a recipe is out of stock at the supermarket – but the outdoors isn’t like the supermarket. What is great is that you can head out intending to pick a particular thing but end-up coming home with all sorts of other things instead. Serendipity is the spice of life.

A few years ago, I was in Scotland with a group of foragers, chefs etc., at the invitation of a whisky distillery. I hadn’t had any alcohol since the birth of my son so I was a little tentative initially but by day three I was able to drink whisky until 5 in the morning and swear undying love to a bunch of total strangers. It was in the early hours of that third day (and after a lot of whisky) that a few of us, realising that we shared similar ideas about our craft, got into the kind of meaty discussion that a coming together of like-minded folk lubricated by peaty drams engenders. On that night that myself, my friend, Andy Hamilton, and another friend, Mark Williams, coined the phrase, “our neglected native spice rack”. Now, I would swear on my mother that it was me. Andy has subsequently published articles that include this phrase, and Mark went on R4 to talk about how he came up with the idea. Anyway, basically, at 5 in the morning, I invented this phrase, “our neglected native spice rack”.

Why are plants so contrary? The reason is that the flavour of the plant is utterly irrelevant to the plant. It’s a human arrogance that there should be a reason. In a similar vein to Mahonia, cherry blossom can taste sweet or bitter or of almond oil essence, or of any three of those combined and in any order. You can pick a cherry blossom and it may taste sweet but then taste of almond. You can then pick one from some 3ft away which will taste like almonds, then taste really bitter. When you start to form a reasonably intimate knowledge with certain plants and when it is that they present different characteristics, then are you able to use them efficiently and effectively, not to mention deliciously and creatively.

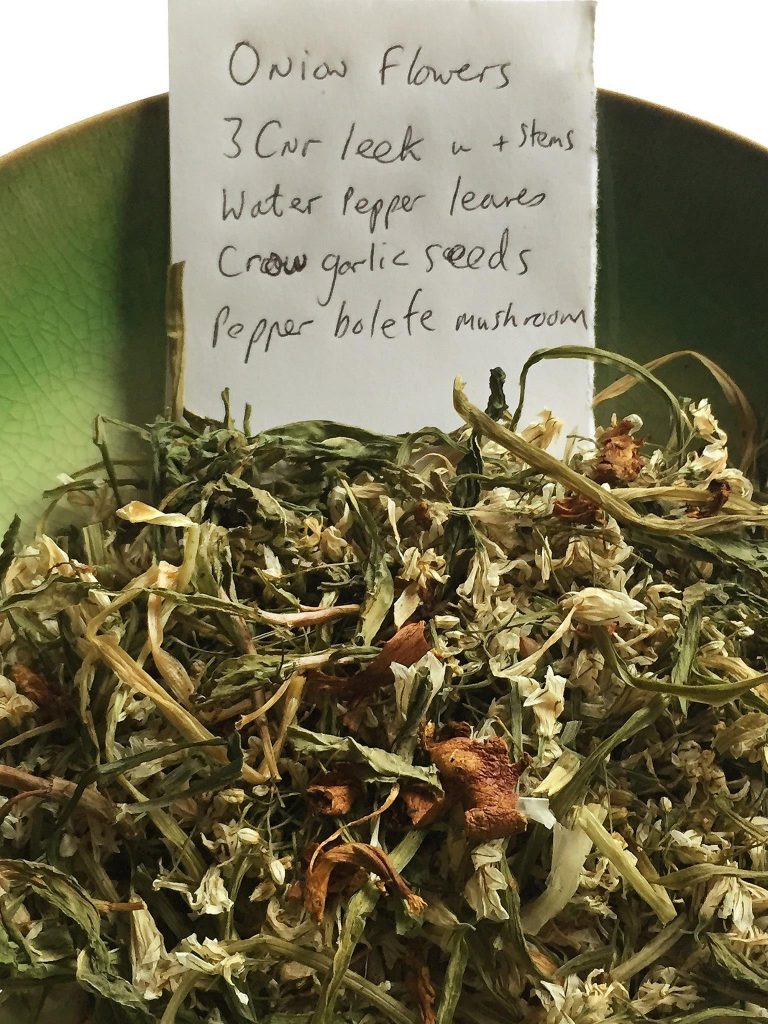

I’ve selected 5 native spices to talk about here but there are many, many, many neglected spices to discover growing wild in the UK. It’s great to cook things fresh, on the spot and equally satisfying to conjure something up in the kitchen with produce you have foraged that day but it’s also hugely satisfying to be able to work with these spices throughout the year and build-up a dry store. Scratching the surface, by way of example, this is the first shelf of my very extensive spice cupboard: hogweed, acorn flower, reindeer moss, wild thyme, fennel, rosehips, water mint, wild marjoram, jelly-ear mushroom, Himalayan balsam flowers, plantains, bog myrtle, lemon balm, wood sage… I could go on but lists are boring.

Now, as a disclaimer, when I say we have a “native spice rack”, what I actually mean is that, from a flavour perspective, we have equivalents of numerous exotic spices that we wouldn’t assume grow in the UK. They don’t exactly match-up flavour for flavour; for example, we don’t have star anise but we have 3 things that you can put together to form something that heads in that direction. Our equivalents often have “more bitterness”. This is partly to do with the plant but is also more noticeable because we are no longer used to such bitter flavours. In almost all cases the bitter flavours have been bred out of things; the rest of the time, we just larrup-in a load of sugar and, interestingly, that’s not necessarily for taste reasons. A good example would be rosehips. These were used an awful lot during WW2 when we needed more vitamin C as they contain more of this weight for weight than oranges. If you look at traditional recipes for jams/syrups etc most come from a time before refrigeration and, more importantly, before freezers, so most contain a s***-load of sugar which is there as a preservative. Now, imagine (and this is very zeitgeisty) that you could make a really, really lovely jam which only contained 20% sugar… (you can, in fact even make a jam with zero sugar by using just the fruit and adding chia seeds).

A traditional recipe which will end-up with more sugar than water, involves taking a wonderful wild fruit – the rosehip, in this instance – that’s full of these amazing flavanoids, pectins, phyto-nutrients, antioxidants and smashing the living s*** out of it with a lot of disaccharide table sugar to make something that essentially tastes pink. The rosehip syrup I make uses about a fifth of the recommended sugar. Once I’ve made it, it won’t keep long enough for me to put it into cutesy kilner jars that I can arrange on my fancy kitchen shelves to show how creative I am, so I put it in plastic bottles and freeze it. It doesn’t taste pink; it doesn’t taste like rosehip jam. It tastes like papaya, mango and tomato. It tastes amazing because I’ve not bashed the s*** out of it and because there’s a wonderful selection of tropical flavours in an English rose. I’m not saying if I gave you a pipet of rosehip syrup and a pipet of mango syrup you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference, the rosehip just has a lot of those things going on in its flavour profile that have been neglected because of sugar. In terms of top-notes though, a lot of plants cross over in this way; for example, bluebells (although poisonous) share a lot of similar aromatic top-notes to mangoes. The crossover arises from the shared plant chemistry. Plant chemistry isn’t exclusive to plant families. There are members of the daisy family, for example, that have very similar chemistry to members of the mint family but they aren’t related. There’s a plant called mugwort which is related to wormwood but that has a very similar chemistry and aroma profile to rosemary and has a lot of essential oils and eucalyptol in it.

If you want to know more about the concept of how we taste bitter, I recommend Jennifer McLagan’s book, “Bitter: a Taste of the World’s most Dangerous Flavour“. She writes really interestingly about this subject. How you taste depends on the number of receptors in your tastebuds, which means that you can either be a non-taster, somewhere in the middle (like a normal person) or a super-taster – someone for whom bitter is really extreme. If you become familiar with these plants, learn what you can do with them and aren’t scared of the concept of bitter then it’s a great way to expand your palate. This is why cocktail makers, or rather, mixologists, are great to go foraging with because they taste the bitter. When you present something bitter to them they’re thinking “hmm, that’s the back-end of a negroni” or “that’s an old-fashioned” – and they start to think about how they can temper this with other ingredients. Your average palate will register, “oh, that’s a bit bitter”.

To return to the point, foraging for wild flavours means that you’re often dealing with more bitterness than you are used to. For the spices below, we’re talking about using one part – the strongest tasting, woodiest part. The following 5 would have had a lot more common usage hundreds of years ago when there was less of a disconnect between our food supply and our cooking and when we didn’t fly food thousands and thousands of miles across the globe.

Wood Avens…. our answer to CLOVES

We are now in the rose family. It’s huge; in fact with c. 25,000 members worldwide, it’s the largest plant family. A lot of our fruit trees – apples, cherries, plums, almonds, peaches, pears are from this family, as is a lot of our soft fruit. Wood Avens is a perennial wildflower; upright and wiry with five-petalled, yellow flowers.

Wood Avens starts life by producing a little trifoliate leaf, a bit similar to a strawberry (to which it is related). It’s a terrible salad plant, awful; hairy and you wouldn’t want to eat it. But, if you become aware of how you can engage with this plant then you will learn that its roots have something wonderful to offer our palates. It’s fancy name is geum urbanum, from the Greek “geno” which means “to give off a pleasant fragrance”. This refers to its roots which are very aromatic and smell like cloves. The urbanum part is Latin for “of the city”. Wood Avens is a very common “weed” in our cities, towns and villages. You have probably walked past it countless times. If you are into facts, then this plant also gets referred to as “Herb Bennet”, which is a medieval corruption of the Latin herba benedicta – “the blessed herb” – the aromatic roots of this plant were worn as amulets to ward-off evil spirits.

Now, if you want to dig the root of this plant up to get to the good stuff then you need to dig it up when it’s not putting all of its energy into fantastic foliage/leaves/flowers etc. You want it when it’s putting its efforts into rootstock and that is during early Spring/late Autumn. It’s important to mention, by the way, that you need to get permission from the landowner to dig-up any plant. When you engage with it properly then you get a plant that has roots with a unique flavour. Wood Avens sometimes gets called “clove root”; this is unfair on Wood Avens because, really, it is its own thing which is why I say it’s a “type” of clove. On my foraging courses, I get groups to try this root. When I ask them what it tastes like, bearing in mind that chewing a clove isn’t exactly pleasant, out of 12 people, someone will say, “it’s really familiar… it’s nutmeg” and then everyone agrees; so I say, “any advance on nutmeg” and someone will say, “cinnamon” and everyone will agree; so I ask again, and someone says “no, it’s cloves!” and, yup, everyone agrees. Now, it does taste of cloves but, to be fair, it actually tastes of its own thing because it tastes of all of these things but it contains eugenol which is a feisty chemical compound you get in cloves.

The eugenol in cloves is also medicinal, of course. You have to wonder with us having a native equivalent of cloves whether the spice trade, wars and genocide would have gone on if they’d known you could dig-up cloves in a domestic English hedge.

Anyway, I collect the root and dry it for various things:

- I steep it in vodka to obtain an alcoholic, clove-y tincture – so it becomes a cocktail ingredient.

- I cook it by gently steeping it in water and sugar then remove the root so I get a clove-root syrup.

- I also make an elderberry and clove cordial which I sometimes use clove root in, and that tastes like Christmas. With that, apart from the sugar, you have a totally native immune-boosting cough-mixture thing going on.

- You can dry the root and then grind it into a powder so you can bake with it for that lovely background depth and warmth that clove brings to cake, biscuits and pies.

- The piece de resistance, however, would be that it features in my native spiced chai. This is like a standard chai recipe but where I’ve worked to mimic all of those exotic flavours (clove, cardamom, ginger etc) with native ingredients. What I found is that rather than mimicking one flavour, native spices dovetailed into two/three. I used magnolia petals for the ginger and hogweed as a kind of cinnamon/sort of allspice. I used fennel and a few other bits and bobs and it’s great! I first made this when I was still living in London. The mad thing is that the flavours of a chai are Indian, “exotic” spices but you can get them in Clissold Park. I could probably have sold – “Clissold chai” on Church Street in Stoke Newington and made a mint.

on the right, John’s wild chai

It’s this intimate knowledge of plant flavours and how they behave which is key to amassing a native UK spice rack. Equally important, however, is an understanding that wild plants contain a lot more phyto-nutrients than plants in our domestic food chain. The latter have not had a lot of their bitterness bred out of them by 400 generations of farming, so when you are making my wild chai, for example, you accept the fact that it will have more bitterness in its flavour profile than a “normal” chai. So, you either go with that and appreciate that my wild chai won’t taste exactly like an Indian chai or add some extra honey or sugar to your cup to bring it back to the level that our modern palate is used to. I have to say it is amazing.

Alexanders… a native version of BLACK PEPPER

This isn’t strictly native. It was brought here by the Romans as a cultivated, domestic crop but it’s become naturalised and it loves our coastal areas. In Spring you will see swathes of it along hedgerows and on the slopes leading down to sheltered coves.

Whether the Romans used it as a pepper or not I don’t know but they would certainly have eaten the upper parts of the plant – the foliage, young shoots etc, raw or cooked, as a general all-purpose vegetable. The version the Romans had 2000 years ago may taste very different to the one we have now; it may have been hybridised multiple times etc. It’s in the carrot family but within this family you find numerous delicious and a lot of deadly plants, so this is definitely not a place for novice foragers to root around. The leaves and buds are like a very perfumed angelica. This is not a flavour profile I enjoy but some people really do. Alexanders’ generic botanical name is Smyrnium Olustratum from the Greek “smyrnion” – “myrrh”. This would suggest that there is an aromatic similarity between Alexanders and Myrrh; however, particularly when Alexanders is fading, it really stinks. The olustratum essentially means “black garden herb” which most likely refers to the seeds.

It produces yellow flowers and all the stems open from a single point like an umbrella. Coastally, especially on any walk-in to Portland (for the climbers reading this), you will pass a ton of Alexanders. Around August, the flowers have gone over and what’s left are the seeds and the plant looks like an inverted umbrella blown-out by the wind (for the poets reading this). The botanical term is umbellifer. Please do not go for a little forage for these – get the wrong black seeds you might be eating poisonous hemlock. When you do get the right seeds, however, you can crush them and they are basically a native-growing black pepper.

Again, think about the spice trade, the peppercorn rate, the value of spices – particularly pepper – all that went on and we’ve already got one! What was all that about?! Admittedly it’s a little more bitter and a little less sophisticated than black pepper. This may be due to a lack of sunshine on our shores which would, therefore, mean the plant produces less sugar; or it could just be that this is what this plant tastes like. This is carrot imitating pepper although, obviously, not consciously and certainly not to please us. It’s not black pepper. It’s not even vaguely related to black pepper. It happens to be something that coincidentally, not to the rest of the planet or to the plants, but to the human palate happens to have a resemblance to pepper.

What do I do with it?

- I use it in my chai.

- My deep love of jerk chicken inspired me to create a native jerk seasoning …my magnum opus! This involved 21 different native plants with which I’ve tried to mimic pimento, allspice, chilli etc. And, among these 21 is Alexanders, whose seeds stand-in for the black pepper. I fell down when it came to chilli (see below) but that’s ok. It’s about availability; so I added chilli.

- I also use it as an actual pepper in a pepper grinder. It has a really strong peppery aroma and taste.

- I sometimes make fishcakes for clients on my coastal foraging walks. I’ll pick wild fennel and sea purslane, and mix these up with the potatoes, mackerel and Alexanders seeds, which are great with mackerel.

Water pepper… a native equivalent of CHILLI

The reason I wanted to mention this is that it illustrates a point. It’s a UK growing chilli… sort of. It’s not related to chilli but it typifies the concept that we have interesting and exotic flavours and spices in the UK that we don’t imagine in a million years that we would have. I will level with you, it’s not a chilli. It’s not as fantastic or as delicious. It amuses me because of it’s crazy Latin name Persicaria hydropiper (although I am most certainly not that man of a certain age who uses long Latin words loudly in public). This refers to its leaves, which resemble those of peach trees, and then to the fact that it’s a peppery plant with a preference for a watery habitat. Water pepper is in the dock family, so vaguely related to dock, sorrel and a few other things. It grows in wet areas in woods.

Possibly the most interesting thing about it is that the old English name for it is “arse smart”, which is actually the real reason I wanted to include it in this list. It used to be incorporated into bedding mix and would give people a burnt bum because it’s hot – the hot it will burn your arse on the outside.

I tried to use this in my jerk spice mix but found that I just couldn’t mimic chilli in its entirety because water pepper has “chilli hot” but not “chilli sweet”. I needed the “chilli sweet” too which I’ve not been able to locate… yet…. Water pepper is harder on the palate than a normal chilli. I don’t mean in terms of heat, I just mean aggressive. Imagine chilli that’s also a bit bitter as opposed to those sweet Turkish chilli flakes. The problem with Water pepper, from a forager’s point of view, is that, like a few other plants, when you dry it, the hot flavour goes and all you’re left with is bitterness so it’s a plant you have to use fresh; you can’t keep it in your store cupboard; frustrating!

Magnolia… the UK’s equivalent of GINGER

Many of us are pretty familiar with these exotic trees. We’ve got hundreds of species of them in the UK and they flower their little backsides off between late January through to late Spring, depending on the variety. We also have 3 or 4 evergreen species (although these don’t taste that nice to my knowledge). Magnolia was named after a French botanist – Pierre Magnol.

In varying degrees, the big, slightly crunchy blossom tastes like a cross between ginger and chicory with a bit of celery thrown in. It is reasonably bitter but happily it loses 50% of this when you dry it.

Basically, you can use Magnolia in any way you would ginger:

- I like to include the fresh blossom in a wild salad. A wild salad is a mish-mash of strong flavours, some aromatic, others sweet or spicy; not like a supermarket salad that smells of farty gas and tastes of basically nothing much at all (maybe cucumber and some mint if you’re lucky). A wild salad can be a real journey. If you just chop-up one magnolia petal and pop it into the salad it brings a really zingy ginger hit.

- You can also dry the Magnolia petals and grind them down to a powder. So… naturally, they are in my chai, my jerk mix, and also feature in a native curry powder I make.

- I’ve used them to make gingerbread biscuits and… my son didn’t know it wasn’t ginger.

- It can be used in syrups and therefore as a drink ingredient.

- You can also pickle whole flowers in rice vinegar, mirin and water (so, not a strong pickle) and you get this delightfully aromatic, gingery, crunchy, Japanese thing going on and it’s therefore great with Sushi!

Hogweed… a type of ALLSPICE/BITTER ORANGE

With this, we’re back in the carrot family. This is an amazing plant and has numerous edible parts.

The young shoots are great steamed or fried in a tempura batter.

If you pick hogweed flowers at the right time you can steam them like little broccoli heads. Hogweed has these lovely unopened flower heads which sit in a sort of diaphanous little sack (if you think of broccoli as a sort of unopened flowerhead).

When the big white flowers fall off they leave the seeds sitting on the plant. Now, here you do really need to know what you are doing in terms of getting it right, but these seeds taste and smell like bitter orange and cinnamon.

John’s “Moondog Martini” (named after Moon the dog is a blend of gin, dandelion flower syrup, apple-mint and hogweed seeds

It’s an appealing and intriguingly complicated flavour profile, making them great for all sorts of things:

- I use them to make syrups and cocktail bitters or for infusing mulled wine.

- They are also particularly good ground-up and used to make a sticky ginger cake or Hogweed parkin!

- I’ve used them in my chai (of course!), my jerk spice mix and in curry spice mixes.

- When you dry-fry the seeds you make more sugars available so you are shifting the flavour profile to a toasted aromatic, slightly sweeter taste so can use them for things that require a gentler “hit”, like cakes, crumbles or sprinkled into a granola mix before you pop it in the oven.

So why should we give time to these native spices? I mean, you can go to the shop and buy a massive great pot of cloves for a quid as opposed to going out in the wind and rain and digging it up, right?. Three words; and I did coin this: “tastebud time travel”. I’ve already mentioned the difference in flavour profiles, but by tasting/cooking with these spices, you are directly tapping into an experience our ancestors would have had hundreds of years ago. The tendency nowadays is to associate English crops and English food with English cooking from the ’60s and ’70s – flavourless; but we have these amazing, neglected spices! There are several reasons for the neglect. Two big waves of the spice trade. Then, during the 1950s, as a result of industrialisation and shifts in our way of living that developed in the aftermath of two World Wars, we handed over the final wave of responsibility for our food preparation to big corporations. 100 years prior to that, there was a seismic shift towards city dwelling. People stopped making their own bread, owning their own cattle/land for cultivating, running their own microbreweries etc. 7000 years before that was the beginning of the disconnect, however, when we moved away from foraging towards agriculture. Now, thankfully (and usefully for me on my courses) we are starting to think more deeply about connecting with where our food comes from.

I hope John has given you some food for thought and will encourage you to think about the concept that English/UK ingredients may not be representative of the “traditional” bad, bland English cooking that we have a rep for. Turns-out we have a fantastic array of flavours in the UK and, very likely, a rich indigenous culinary history in that sense; and could do again if we were more aware of what’s available and knew how to use it.

You can find more articles and recipes by Hels’ Kitchen here

And follow her on Instagram